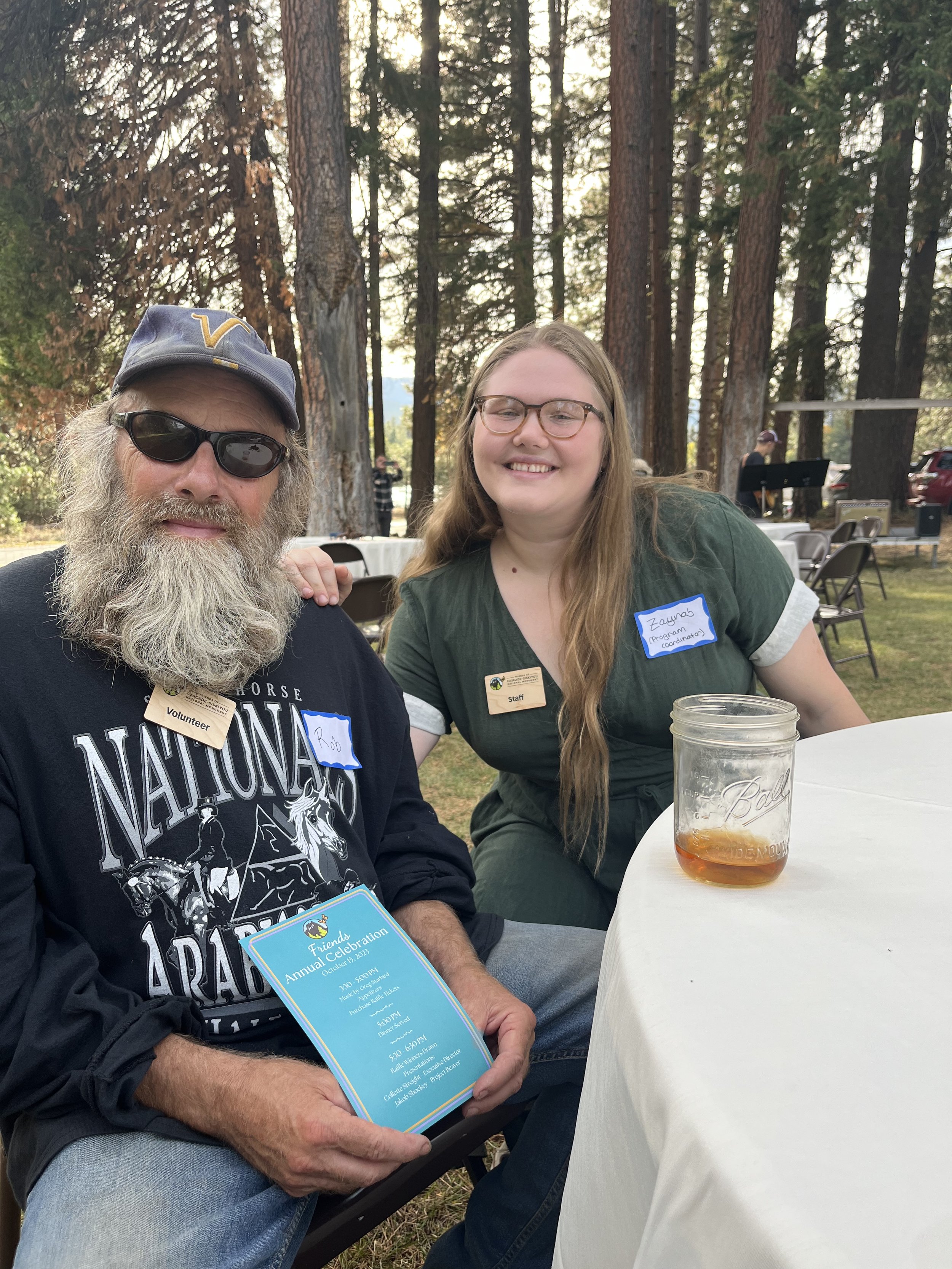

By: Zaynab Brown

Every year, the Friends of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument is delighted to award a number of grants to undergraduate and graduate students and Indigenous Americans for faculty-supervised research projects that enhance the understanding, appreciation, preservation and/or protection of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. These research projects can, and have, taken many forms including in the realms of biology, environmental sciences/education, sociology, arts, humanities, and business.

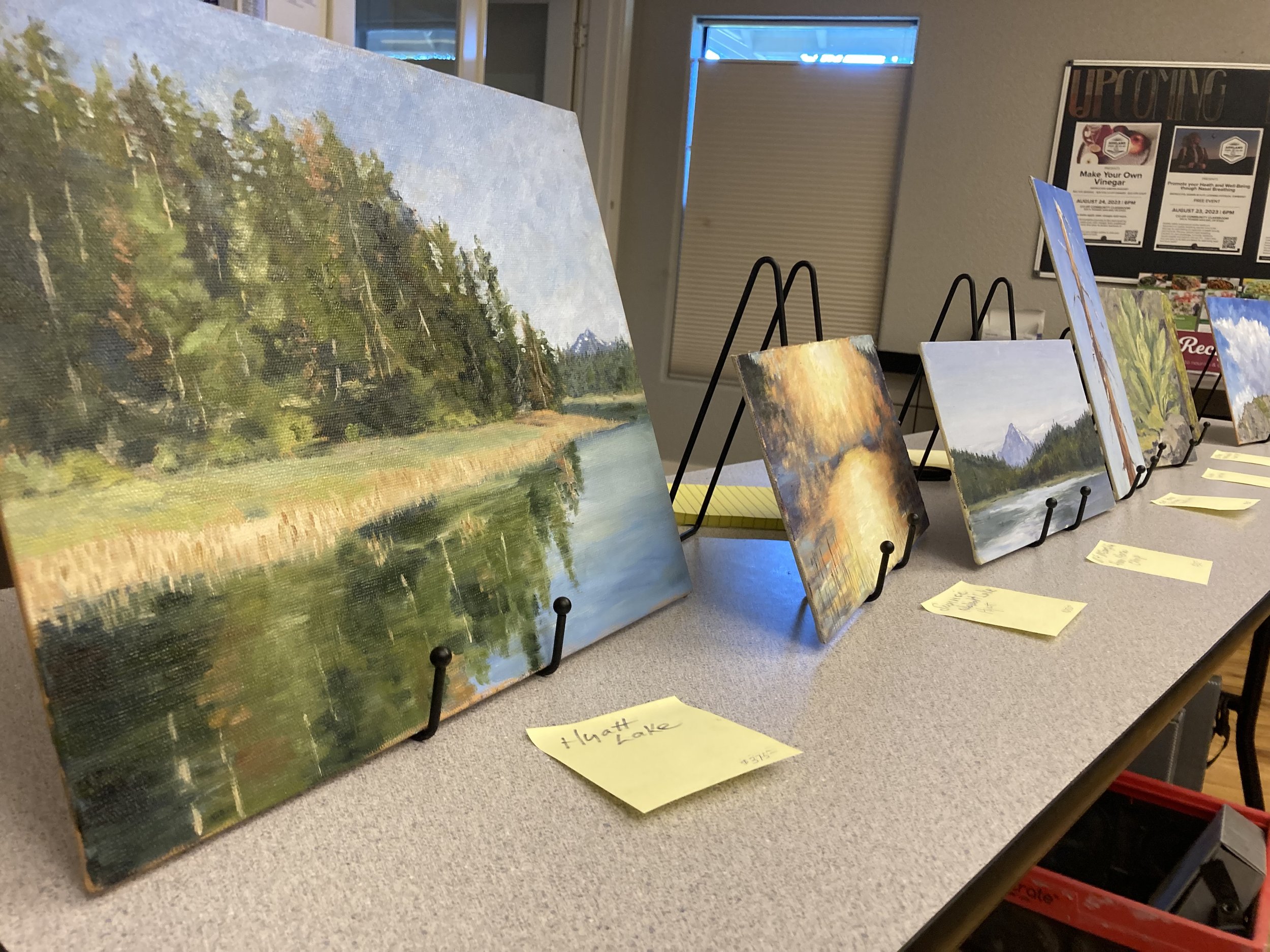

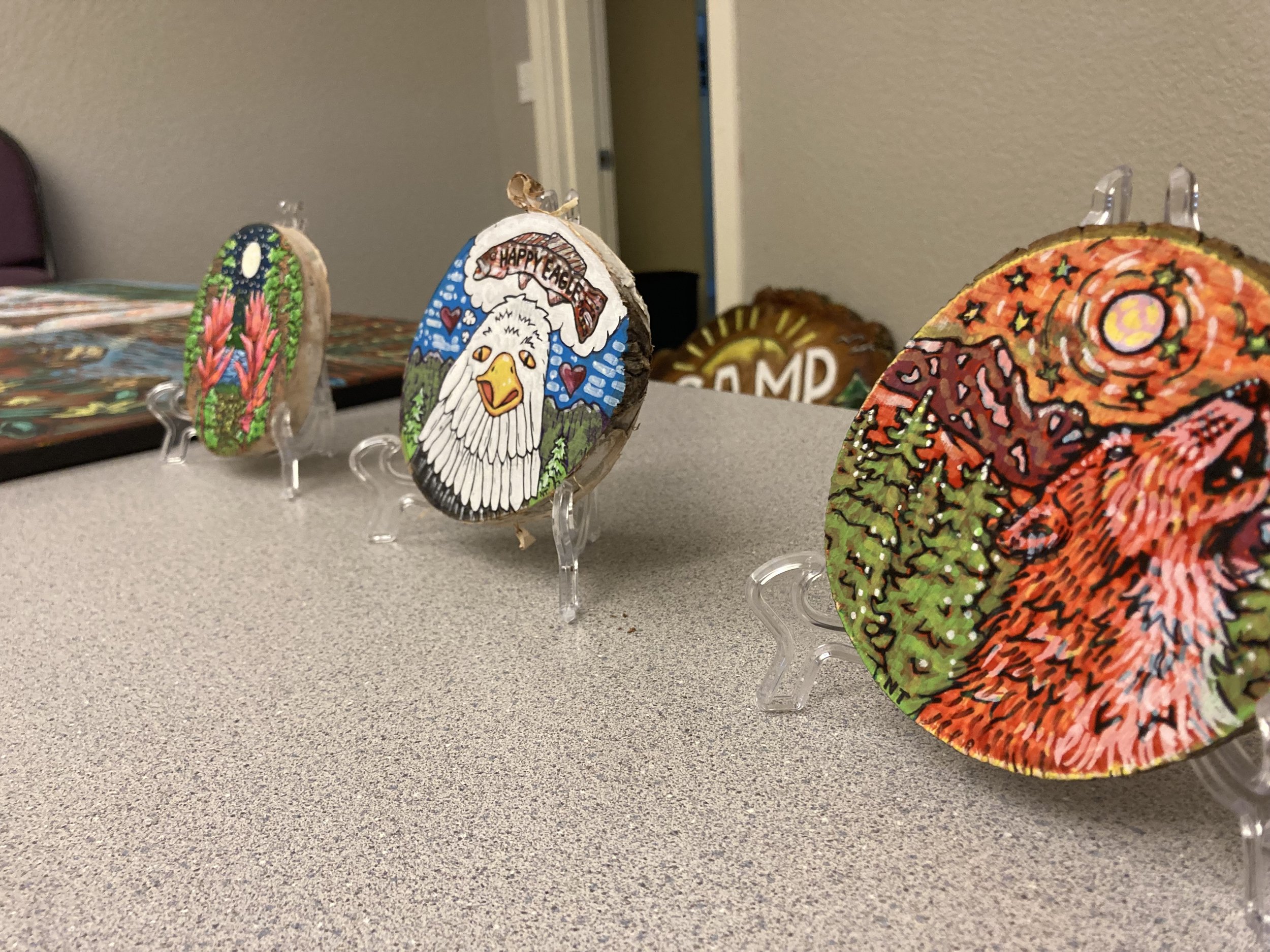

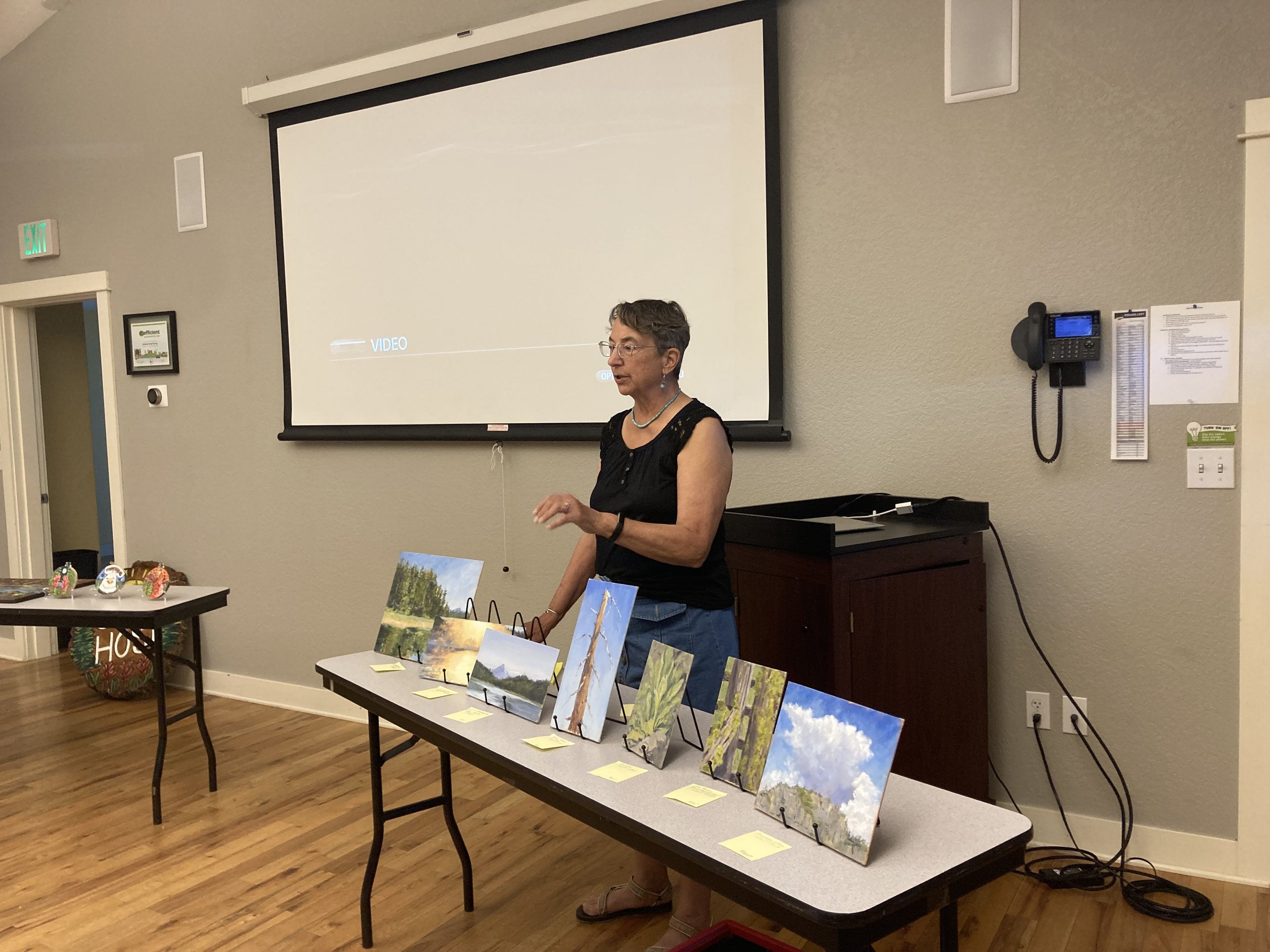

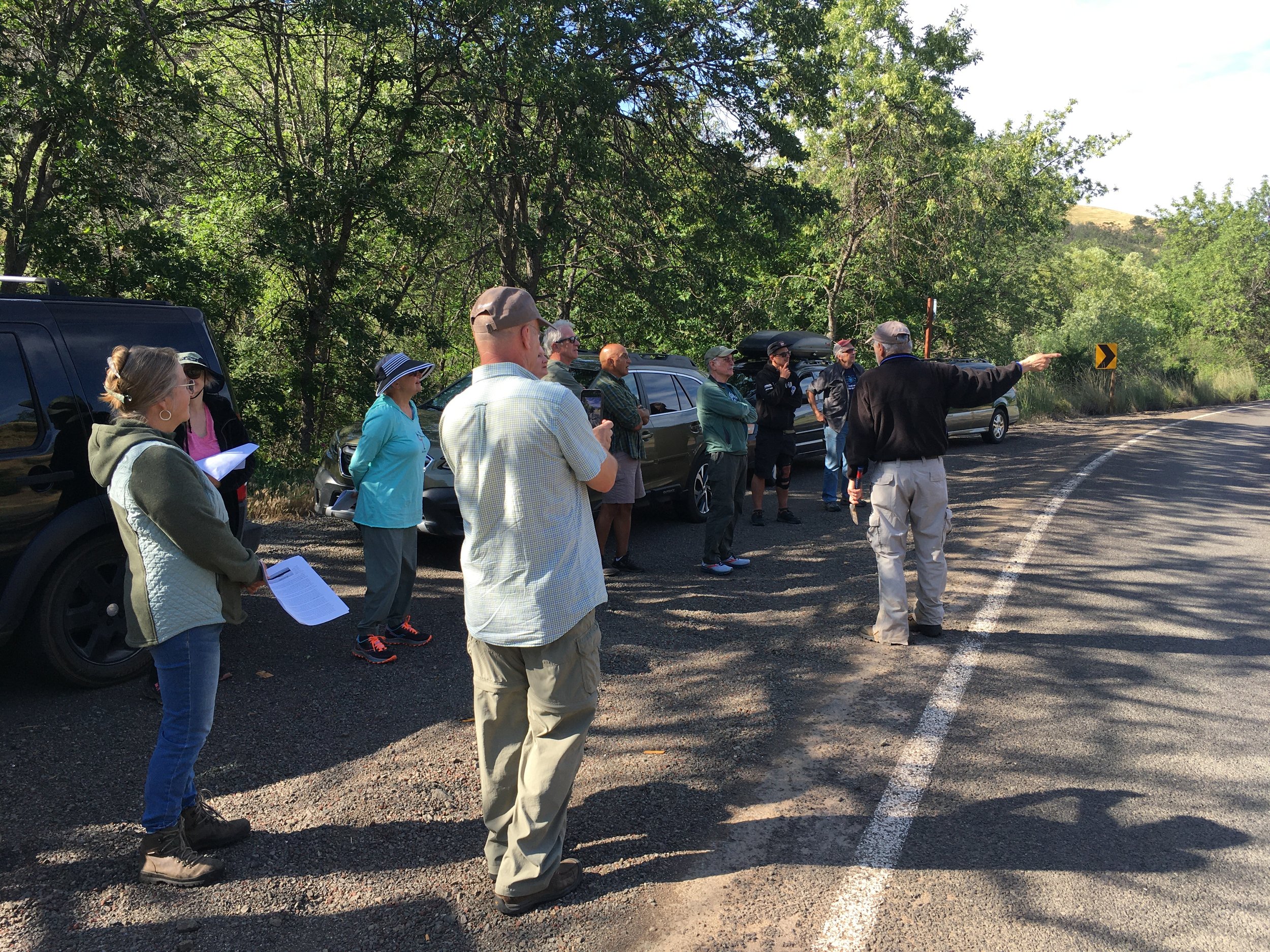

An essential component of receiving this grant is the presentation of the students’ research at our annual Monument Research Symposium. This research represents many hours spent in our beautiful Monument gathering data and then countless more analyzing it. To ask our three grant recipients from 2023 to distill all of their findings into a 20 minute presentation is no small feat, but they delivered with flying colors.

Our first presenter, Trevor Holt, is a senior biology major at Southern Oregon University. He worked with his advisor, Dr. Jacob Youngblood, to catalog grasshopper species found in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument and pilot a long-term monitoring program. Both of these objectives were designed to better understand grasshopper biodiversity in the Monument in the face of climate change and human development. Monitoring grasshoppers is important because they are a keystone species, the most abundant grassland herbivore, and comprise a diverse biology in many diverse habitats. When it comes to climate change in particular, we learned that grasshoppers can be an important indicator species due to the fact that all of their life stages are dependent on temperature, from hatching to feeding, movement, and population growth. With that in mind, some grasshoppers are more adept and hardy while others, such as the endemic Siskiyou slant-faced grasshopper (Chloealtis aspasma) is more vulnerable to change and to the threat of becoming isolated. With over 2000 individuals collected and identified, Trevor proved what many would have suspected: The Monument is rich in grasshopper biodiversity with over 17 species found in his study! As the monitoring program continues into the future, Dr. Youngblood and his team hope to monitor at lower elevations and analyze the relationship between populations and weather.

Grasshoppers (and a spider!) perched on the edge of a collection net.

Photo by Trevor Holt

Our next presenter, Tayla Moore, used her Monument Research Grant to focus on a single grasshopper species, the aforementioned Chloealtis aspasma. Tayla is also a senior biology major at Southern Oregon University who worked with her advisor, Dr. Jacob Youngblood to map the distribution of C. aspasma and uncover its natural history. C. aspasma, as mentioned above, is also called the Siskiyou slant-faced grasshopper. While Chloealtis species are widespread in North America, C. aspasma is endemic to Southern Oregon and potentially Northern California where they are designated as a species of concern by the Bureau of Land Management and United States Forest Service. They live in open fields and meadows at high elevations and their dispersal is limited by smaller wings and their preference for high elevation, mountainous regions. In total, Tayla was able to visit 26 sites within the Monument and found C. aspasma in ten. Of these ten, five were previously undocumented populations. Unfortunately, observing this elusive grasshopper’s natural history proved to be more difficult and further research will need to be done to uncover more information on its feeding, reproduction, and thermoregulation patterns.

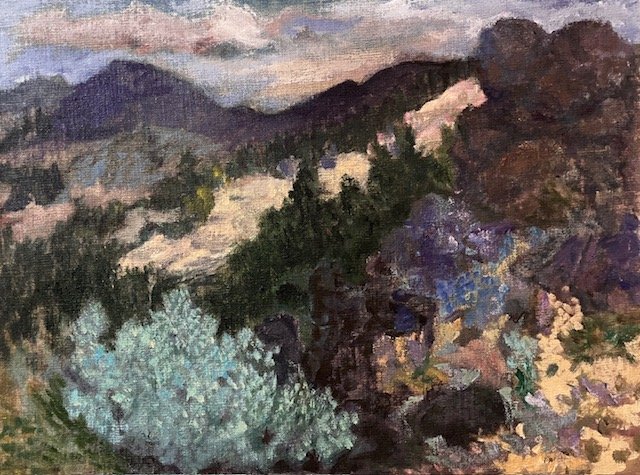

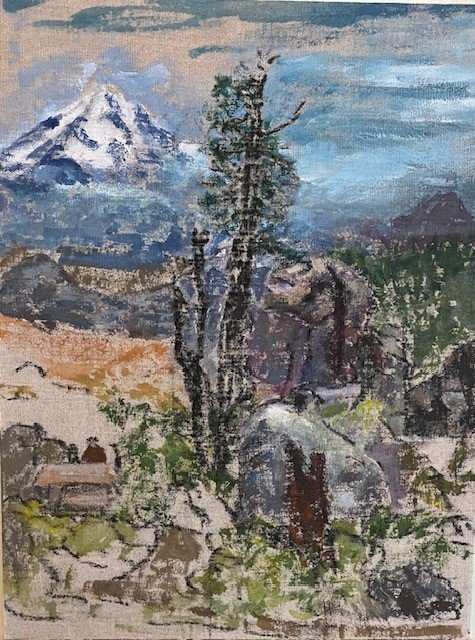

Chloealtis aspasma

Photo and annotations by Tayla Moore

Finally, our third presenter, Hilary Rose Dawson, a Ph.D. candidate from the University of Oregon, joined us for a second year in a row to explore truffle species found in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Now, most people’s experience with truffles begins and ends in a culinary context, and while there are certainly a handful of culinary truffles found in Oregon, we also learned about the fascinating diversity of non-culinary truffles found just below the surface. These truffles have scents ranging from artificial banana to burnt rubber and serve a variety of essential ecological functions. However, humans aren’t exactly known for their sensitive noses so it was essential for Hilary –aided by her sister, Heather Dawson–to employ a canine friend named Rye. In 2023, they visited almost 30 sites in the Monument and found 57 species across 26 genera, an incredibly diverse range! Of these, 32 were not documented in genetic databases making them potentially undescribed species. Hilary hopes to finish sequencing and finalizing the list of truffle species found in the Monument and ultimately publish a paper on the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument’s truffle diversity and a case study on how truffle dogs can be used in truffle research.

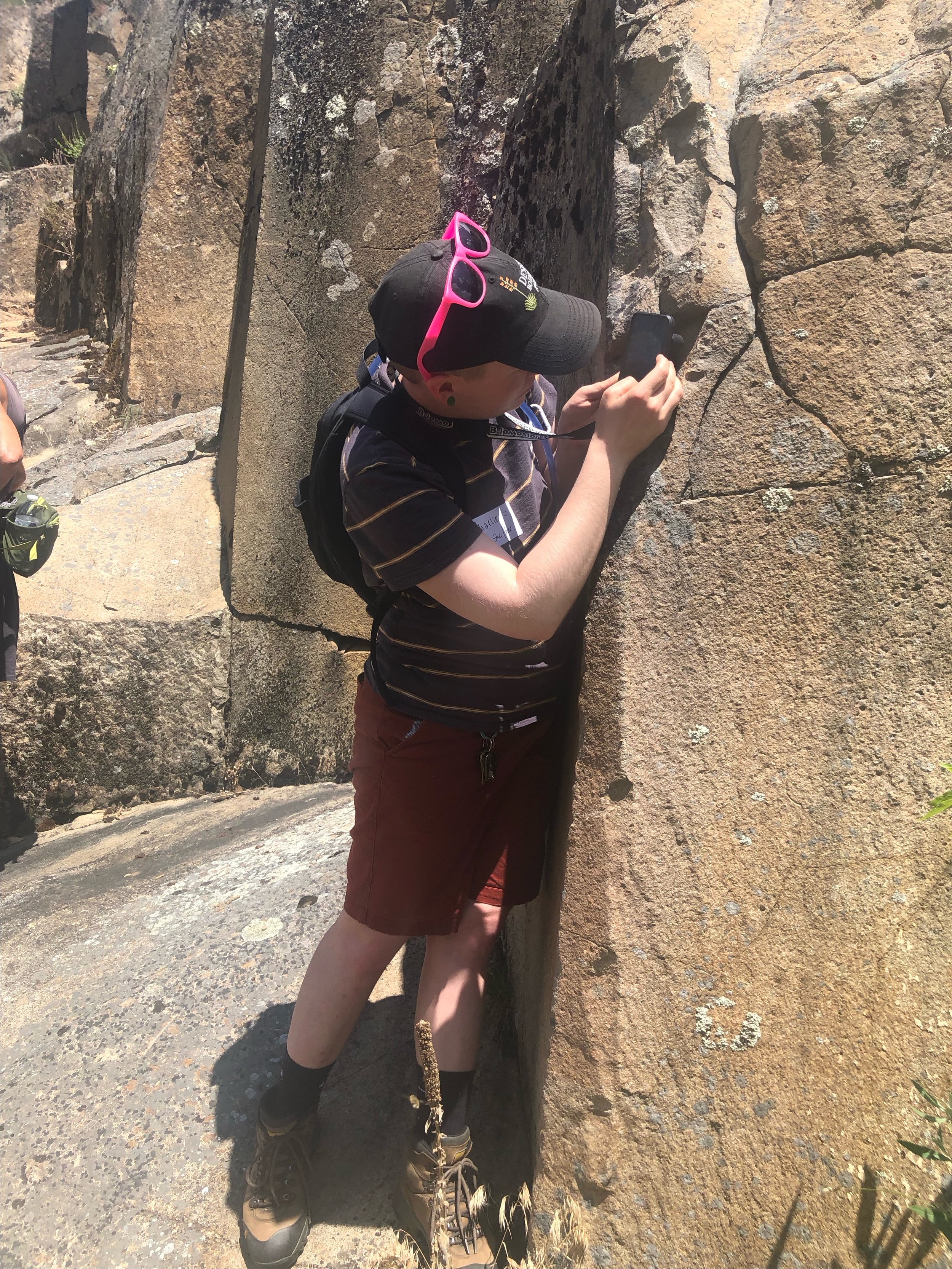

Heather Dawson photographs a Hysterangium truffle while Rye waits for her to throw the ball again. Photo by Hilary Rose Dawson

If you are interested in learning more about these projects, the symposium can be watched in its entirety on our YouTube channel at https://www.youtube.com/@friendsofthecascade-siskiy4103

With our 2024 Monument Research Symposium a resounding success, we are looking forward to getting to experience the unique projects that students will propose for this coming grant cycle. Applications are now open and information can be found at https://www.cascadesiskiyou.org/programs . The deadline for applications is April 26 at 11:59 PM PST.