By: Zaynab Brown

For most people, when we experience nature we experience it through the lens of a human. This is, of course, to be expected. However, in learning about wildlife tracking, you not only learn to differentiate between a feline and canine paw print but are also invited to see the world from the perspective of an animal. While the animal is absent, you get a snapshot into a moment of his/her life as he/she navigates the world. Maybe you observe that the animal is trotting and ask yourself “why?” or “where?” Why was it that the coyote decided to detour around the ravine and what did he find there? What did the trees look like from his perspective? Needless to say, we can’t know the true answers to these questions but in the process of considering them we may begin to look at the environment around us differently. We may notice things that before had seemed too small or insignificant to grab our attention. Suddenly, the world is much more fascinating.

To begin this fascinating journey into the world of animal tracking, we started in a classroom. Admittedly, this is less exciting than a forest floor or open plain but humans are strange creatures. Our instructor for the Friday lecture and Saturday hike was Nolan Richard, a biology teacher at South Medford High School who currently holds a Level 3 Track and Sign Certificate from Cybertracker International.

Together, in a group of almost thirty participants, we learned to identify paw prints belonging to cats, such as bobcats and cougars, and dogs such as coyotes and foxes. We examined the subtle differences in the orientation of their pads and the presence of claws. We saw large bear tracks and discussed the differences between elk and deer. We even learned how to use our own hands to determine the left and right orientation of what had initially appeared to be identical images. Together, we examined rubbery casts of prints and attempted to identify the animal who had made them. Some were from our area, such as the skunk, beaver, and mountain lion. Others however, like the massive grizzly bear, we were unlikely to see in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument (or in Oregon at all for that matter!)

Rubber-like casts of prints. #11 is a grizzly bear.

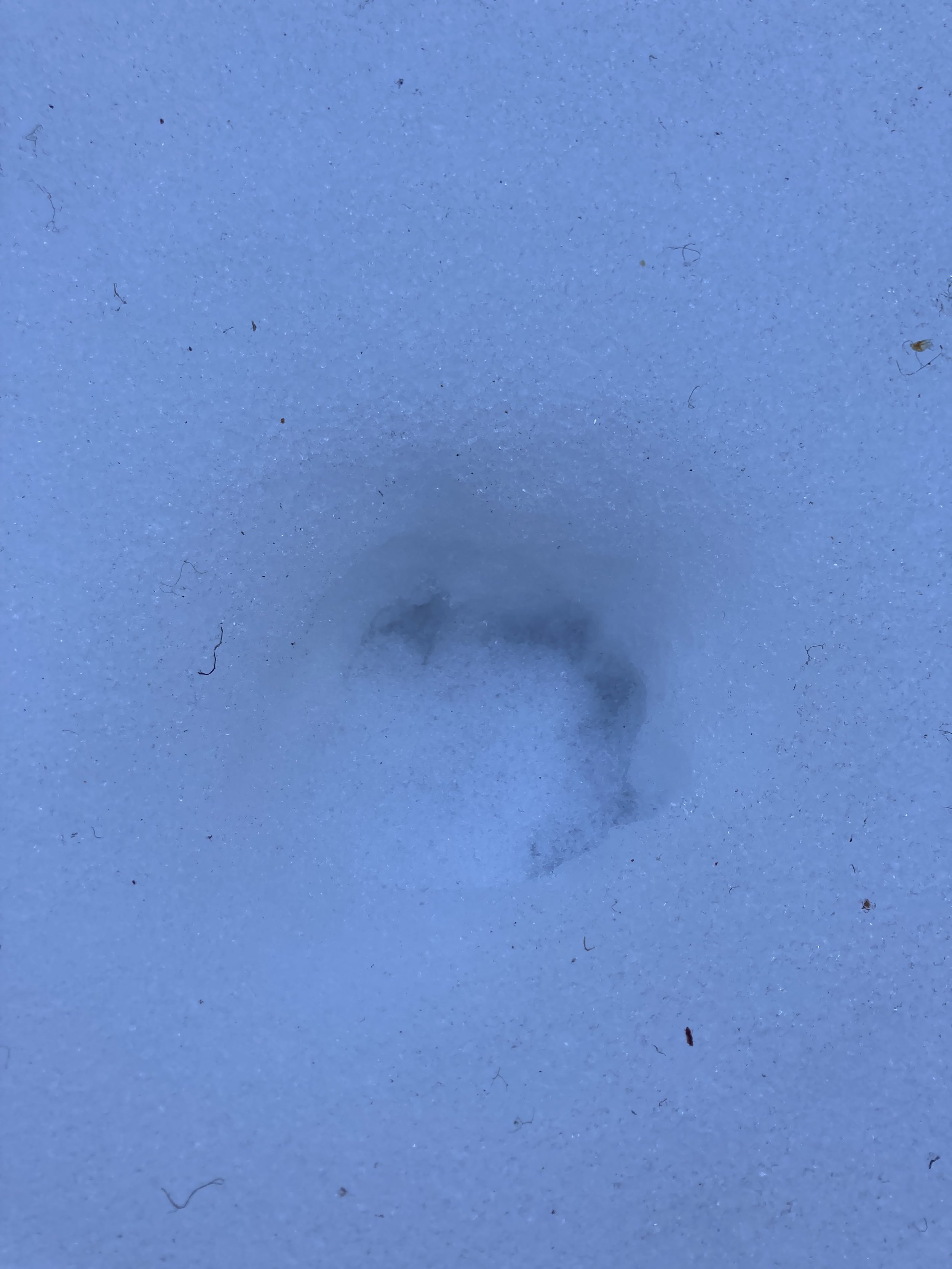

Armed with this new knowledge, we met on Saturday excited to find some tracks and put our burgeoning skills to the test. Although we quickly learned that when it comes to tracking, some conditions are better than others. In a perfect world there would be powdery snow, not too deep and not too recently fallen. We don’t live in a perfect world however and the snow we had was icy and hard. While this will allow some larger animals to still leave tracks, most animals will simply walk on top of it without leaving a trace. But this didn’t stop us and soon we found coyote tracks snaking through a small meadow and many deer tracks. These prints, while not pristine, could still tell us a story if we looked closely enough.

An important thing to remember, especially when looking at tracks that lack fine detail, is to consider the environment around you coupled with knowledge about local species. Some species, while abundant at lower elevations –such as a skunk– are much less likely to be found at higher elevations. Or, if you are looking for snowshoe hare tracks, they are much more likely to be found around tree cover than out in the open.

Finally, it is not only tracks that animals leave behind! There is also a whole world of “animal signs.” Perhaps most well known of the animal signs is scat, or feces. Our group discovered lots of scat when we visited Buck Prairie Two. We learned to differentiate between smaller deer scat and larger, more irregularly shaped elk scat. The scat can also tell you a lot about the diet of the animal that left it. For example, a domestic dog that primarily eats processed food will have scat that is very uniform in texture while that of a similar-sized animal such as a coyote or bobcat will usually contain fur or bones. Our group also found squirrel middens –mounds of discarded douglas fir cone debris, elk rubs, old beaver chews, holes made by a pileated woodpecker, and lots of browse.

Near the end of our hike, we stumbled upon some of the most detailed tracks yet. Four clear toes with claws and a heel pad were starkly visible and the animal that made them was slowly plodding in a direct-register walk where the back foot directly replaced the front in the same print. Participants were suggesting a large coyote or maybe even a cougar! The answer turned out to be much more mundane. It was a domestic dog. According to Nolan, dog tracks are some of the most common you find, especially if you are at a location that humans frequent. Since domestic dogs range extensively in size and shape, it can be almost impossible to differentiate them from their wild counterparts. This is why, Nolan reminded us, that it is especially important to pay attention to your environment. Are there human boot prints nearby? Is it near a road? In these circumstances, always assume it’s a dog.

Dog or not, I couldn’t help but imagine the way the animal saw the world as it walked through the peaceful forest and left prints in the crunchy snow. Did he/she also notice the squirrel middens and smell the elk scat, or take note of the way the snow glittered in the afternoon sun? We’ll never know but we can imagine.