Monument Days 2025: A Season of Discovery and Connection

By Daniel Collay and Ranger Emma Lutz

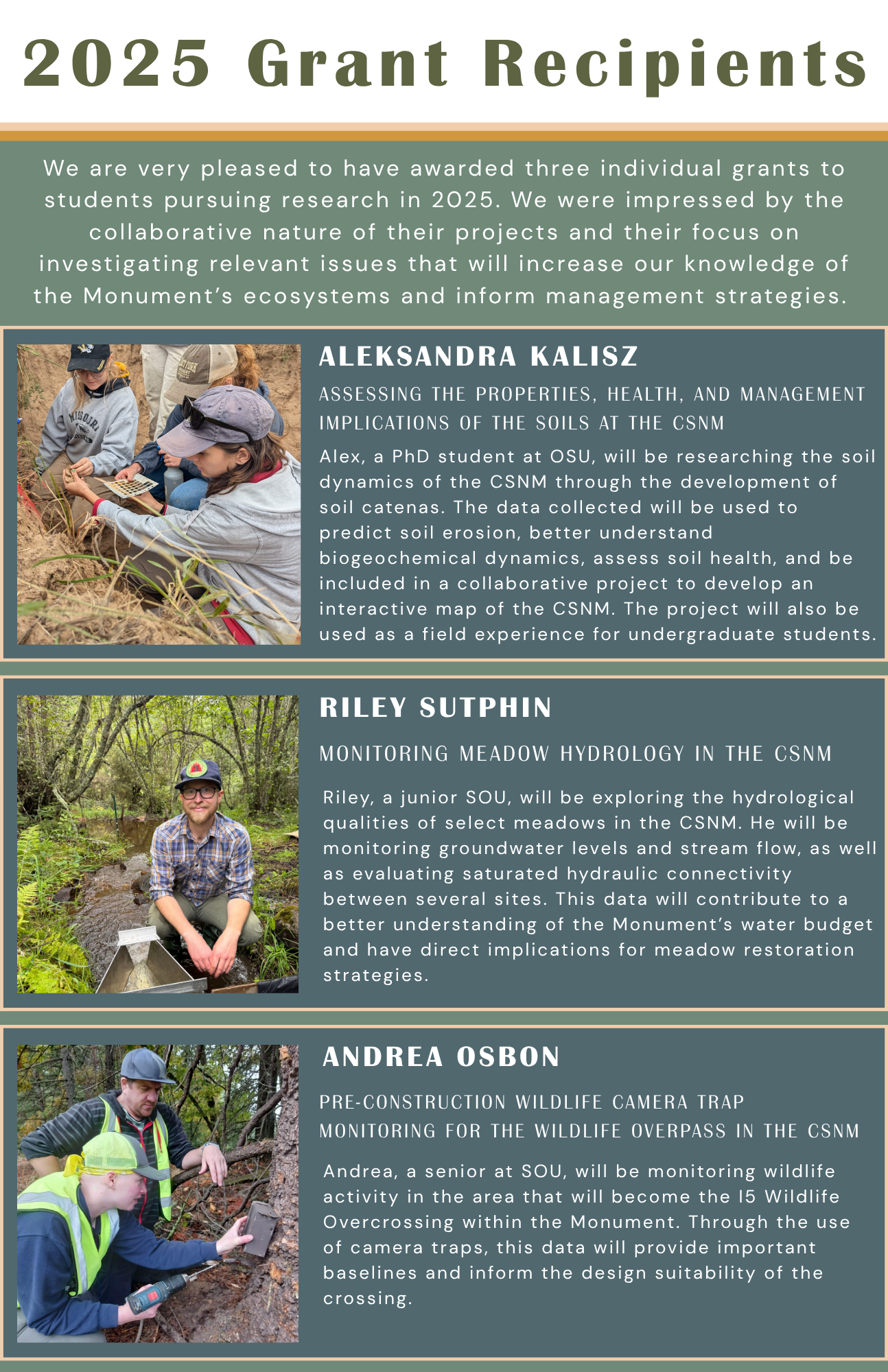

This summer marked the fourth year of Monument Days, a partnership between Friends of Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument and The Crest, made possible with generous support from the Gray Family Foundation, which helps sustain youth education programs. Every Wednesday campers from The Crest’s Summer Nature Day Camp joined our interpretive rangers on excursions in the Monument to connect with its immense biodiversity. Since its start, the program has connected hundreds of children with the Monument. This year, 214 young learners participated in hikes, games, and creative activities designed to spark curiosity and connection with the natural world.

Reflections from Ranger Emma

Campers ages six to eleven were led through conifer forests and oak grasslands along the Green Springs Mountain Loop Trail. They shook the hands, or should I say the needles, of white firs, Douglas firs, and ponderosa pines, and learned that the difference between white and black oak is the shape of their leaves’ lobes.

Games involving echolocation and hawk-like eyesight were played throughout the hike, giving campers a new perspective on how wildlife navigates the world and helping to build up an appetite. Lunch came with a sweeping view of the Rogue Valley, where we identified Mt. Ashland, Pilot Rock, and the soon-to-be wildlife corridor across I-5. This time was also used for solitude, nature journaling, and, whenever possible, lizard hunting.

Walks back were often quieter than the way out, but the discovery of wild strawberries, thimbleberry, and miner’s lettuce along the trail always brought smiles. Back at our base camp, the afternoons were filled with storytelling, fort building, and lots of watermelon.

Thanks to everyone who made Monument Days 2025 possible. With each passing year, the program continues to grow, inspiring the next generation of stewards for this incredible place. We are especially grateful to our partners at The Crest and to the Gray Family Foundation for making this program possible

Campers explore the meadow along the Greensprings Loop Trail

Nurturing Native Plants : Ethnobotany Walk Blog Post

Hikers gather with interpretative ranger Jay Ryan sharing indigenous history in the CSNM - PC: Rianna Shiree

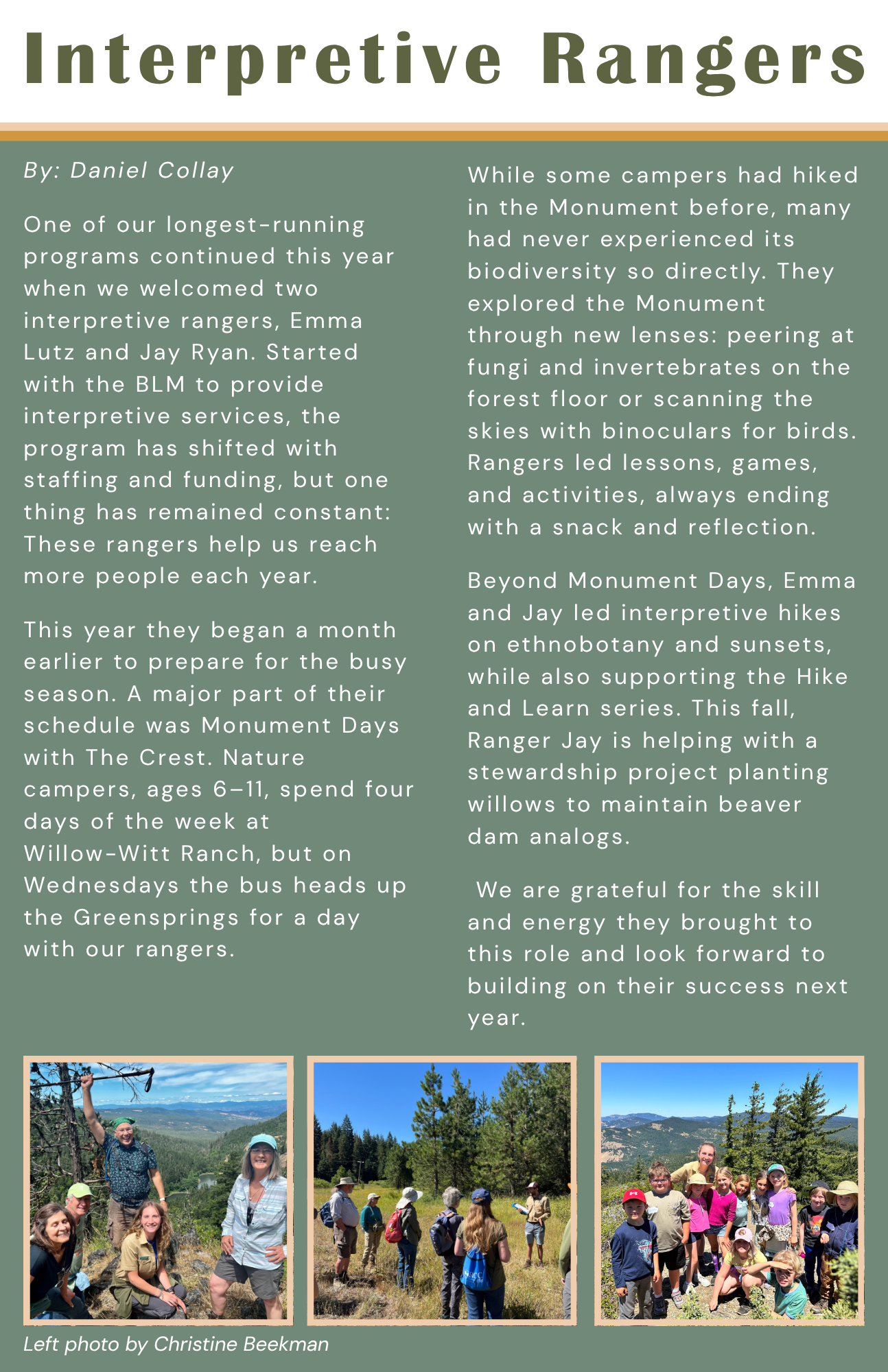

On Sunday July 27th, a group of about 15 participants joined Interpretative Rangers, Jay (the writer of this post) and Emma for an ethnobotany hike. The group hiked along the PCT from Little Hyatt Lake, south towards Hyatt Meadows. Along the way we encountered a variety of plant communities, including riparian meadow, mixed conifer forest, oak savannah, and dry meadow. Along the trail we made various stops to discuss ethnobotany, and I am going to share some of them in this post with you today! First, we will give an overview of indigenous removal from these lands, and why many ethnobotany traditions aren’t widely practiced today. Then we will dive into uses of camas and yampa for food, and beargrass and hazel for basketry, followed by discussion on how fire is used to manage landscapes where these plants grow. Lastly we will offer a species list of the plants that we explored on the hike, and some additional resources for finding more information!

Ethnobotany is the study of how indigenous people use plants for cultural purposes, such as food, medicine, basketry, ceremony, and more. Indigenous people have been living in Oregon since time immemorial and using plants for cultural purposes. What we call the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument is within ancestral territories of the Takelma, Latgawa, Shasta, Klamath, Modoc, and other peoples, all of whom had various ethnobotanical practices. Unfortunately, many of these ethnobotany practices, among other cultural practices such as languages and customs were stolen and criminalized through assimilation and genocide.

Following settler colonialism – to a large extent the gold rush – these groups were forcibly removed from their lands and/or restricted from cultural practices. Due to competition for various resources, such as water, land, and food, settlers drove out native people. Environmental disturbances from livestock and pollution also had significant impacts. For example, Takelma peoples’ camas meadows were destroyed by an abundance of livestock hogs that would dig up the camas bulbs (more on camas later), and Shasta peoples’ salmon fisheries were damaged by effluence from gold mining. Takelma, Latgawa and Shasta people were removed to the Siletz and Grand Rhonde reservations on the coast in NW Oregon. Now the living descendents of the Shasta, Takelma, and Latgawa peoples are members of the Confederated Tribes of the Grande Ronde Indians and Confederated Tribes of the Siletz Indians. The Klamath and Modoc people were removed from their lands and placed on a reservation in the Upper Klamath Basin, which was economically successful through ranching and timber industries, but lost their federal recognition as a tribe and therefore lost their reservation.

For a more thorough history, Please see the tribal websites for the Klamath Tribes, Shasta Nation, and for a history of Takelma and Latgawa, see Confederated Tribes of Siletz, Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde's webpages, or the BLM’s Publications.

Because these indigenous groups had no written language, through this tragic history of forced removal, assimilation, and outlawing of cultural practices, much of their ancestral knowledge was stolen from them. Despite this, the knowledge and practice of many traditions remain strong today, including ethnobotanic practices.

First Foods: Camas and Yampah

Our first stop was in a riparian meadow adjacent to Keene Creek, downstream of the dam at Little Hyatt Reservoir. Here we found remnants of camas seed pods, and discussed first foods. Foods are means of nutrition as well as a way of life for indigenous people. While plants like camas (Camissia) and yampah (Perideridia) have historically grown abundantly, meadows containing these plants are managed to produce higher yields of foods.

Camas and Yampa are examples of geophytes, or plants that have an underground storage vessel. These are perennial plants that spend the growing season pumping nutrients into these vessels for overwintering. Then, when spring arrives and temperatures warm, the plants have the food they need to put up leaves and flowers right away. We can find many geophytes in the grocery store such as potatoes, carrots, or onions, or in our gardens such as tulips or daffodils. Geophytes come in a variety of forms such as corms (garlic), roots (carrots), bulbs (onions), tubers (potatoes), and rhizomes (ginger).

Left: Camassia quamash (great camas) - PC: Steve Thorstead

Right: Toxicoscordion exaltatum (death camas) - PC: Barry Breckling

Camas, known by many as “indian potatoes” is a starchy tuber with a brilliant blue and purple flower. While a different family entirely, camas tubers and leaves resemble those of death camas (Toxicoscordion exaltatum), which is highly toxic, as the name suggests. When gathering, people wait until the plant has gone into full flower, as the flowers of the plant are distinguishable. Joe Scott, a member of the Confederated Tribe of the Siletz Indians, runs the Traditional Knowledge Inquiry Program (TEIP), and is featured in a Buffalo’s Fire article about camas preparation. In this article, they describe how camas is prepared, first by removing outer papery leaves, then baking in an earthen oven for 1 - 4 days! This converts ⅓ of the starchy mass to tasty fructose. Still, many settler’s accounts of eating camas, like those of Lewis and Clark, have ended in stomachaches and restless nights. While traditional methods are still practiced today, camas is often cooked for several days in a slow cooker.

Periderida bolanderi (yampah) - PC: Gary Monroe

Later in the hike, around lunchtime, we visited a dryer meadow, known as Hyatt Meadows, where another first food, yampah, grows abundantly. Yampah is also a geophyte, this one in the carrot family, Apiaceae. In 2019 the Siletz Tribal Youth Development and Healty Traditions program visited nearby Vesper Meadow to reconnect with tribal traditions, and described their relationship with yampah, a name that comes from the Paiute word ya-pah for “water is here.” Just like carrots, yampah roots are eaten roasted, boiled, raw, or dried. The roots have medicinal use too! An infusion (tea) made from the roots is used to wash sores and wounds and clear mucus. A poultice of roots reduces inflammation, and a poultice of seeds can treat bruises. Chewing on the roots can ease sore throats and coughs. Yampah is harvested during dormant season and stored in sand at a cool 38˚F. According to Mt. Pisga Arboretum, it is harvested in late spring or early summer when the soil is soft. The roots are cleaned at digging sites to ensure rootlets return to the soil. Seeds are also left behind, in hopes that they will germinate. Additionally, to help the plants grow, yampah tenders pull competing species out of the way when digging, and seeds are scattered on the ground during ceremony.

Weaving: Beargrass and Hazel

Midway on the hike we passed through a dense conifer forest, primarily composed of Douglas-fir trees. In the understory, beargrass (Xerophyllum tenax) grows abundantly. Beargrass is a common plant used for weaving baskets that is widespread in North America, and is even traded for outside of its native region. The US Forest Service put out a great report about beargrass, titled Natural and Cultural History of Beargrass. Beargrass’ strong and flexible material makes it good for weaving, but baskets aren’t just for holding things. Basketry is “a sacred practice that is important to maintaining the role of certain entities in our lives and recording our History,” said CHiXapkaid, Skokomish Traditional Bearer of Southern Puget Salish Culture and Professor at Washington State University. Basketry and baskets carry the identities of the families who weave them. Beargrass is also used for regalia in ceremony, but the use of this is less widespread, fairly local to Northern California and Southern Oregon indigenous people. There is an excellent video of how beargrass regalia is used, however the presenter is unnamed (you can see my comment hoping to find the creator). Klamath mountain peoples make braids to hang from dresses and necklaces, to make men’s quivers and aprons, and it is stuffed in headrolls. Additionally beargrass gets wrapped around leather strips with berries and shells attached. These make a lovely shaking sound when worn by a dancer.

Left: Xerophyllum tenax (beargrass) in flower - PC: Keir Morse

Right: beargrass basket - PC: Frank Lake

The abovementioned report on beargrass describes harvest practices as well. Beargrass is best harvested following snowmelt in late spring early summer, with preference for high elevation and low shade leaves, as they are less brittle and more pliable. 3-7 years after wildfire or cultural fire is an ideal time to harvest. Cultural burning promotes rigor and growth of beargrass. Gatherers have a preference for longer, thinner, more pliable leaves that are whitish at the base. Only the longest leaves from mature plants are selected, to keep the plant in good health for subsequent years. Following harvest, leaves are cured in the sun for 1-3 days. Letting them dry for too long will leave them dry and brittle. Often beargrass is dyed with wolf lichen, oregon grape, and other natural dyes, but with modern things as well, such as Koolaid!

While we didn’t see any on the hike, Hazel (Corylus cornuta) is another plant that is used for basketry, as well as food! Hazelnuts are widely consumed and tasty when roasted. Hazel sticks are great for basketry, as they are flexible and rigid. Similar to beargrass, hazel responds well to fire. News outlet KLLC out of Eugene reports on how the TEIP uses fire to manage hazel, interviewing father and son Drew and Jerome Viles. In many places, cultural burning or broadcast fire on the landscape is not possible, because it has been outlawed and/or puts homes at risk. Jerome says, “Hazel has evolved with fire. When burned, plants sent up long, straight shoots.” His father, Drew says that “Hazel likes to be coppiced, or cut, it puts up good shoots after it’s been coppiced. Good sticks come two years after burning.”

Corylus cornuta (hazel) - PC: Keir Morse

Beginning of a hazel basket - PC: Bill Barr, KLLC

The aforementioned plants: camas, yampah, beargrass and hazel, have all been managed by cultural burning for millennia. Many camas and yampah meadows were formed during glaciation, and periodically were burned to keep them open and free from conifers. Similarly, beargrass and hazel rely on burning to put up fresh leaves or stalks. When indigenous people were forcibly removed from the landscapes, cultural burning was outlawed, and a paradigm of fire suppression existed in our forests, these plants suffered from a loss of these ecological forces they relied upon for growth. Today, cultural groups such as TEIP, Lomakatsi Restoration Project, Cultural Fire Management Council, and the Rogue Valley Prescribed Burn Association work in the Klamath, Siskiyou, and Cascade mountains to advocate for and implement cultural burning, prescribed burning, and fire mimicry. We encourage you to visit these sites and advocate for a return of fire for cultural and ecological purposes.

These four plants were just a few plants that we discussed on the hike, for a complete species list, see below!

Species List

Forbs

Achillea millefolium (yarrow)

Camassia leichtlinii, C. quamash (camas)

Lomatium spp. (biscuit root)

Perideria spp. (yampah)

Potentilla gracillis (slender cinquefoil)

Wyethia angustifolia (mule’s ears)

Xerophyllum tenax (beargrass)

Shrubs

Amelanchier alnifolia (serviceberry)

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi (bearberry, kinnikinick)

Corylus cornuta (hazel)

Mahonia spp. (oregon grape)

Sambucus mexicana (blue elderberry)

Salix spp. (willow)

Trees:

Alnus rubra (red alder)

Calocedrus decurrens (incense cedar)

Pinus ponderosa (ponderosa pine)

Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas-fir)

Quercus kellogii (black oak), Q. garryana (white oak)

Further Reading

For more information on ethnobotany and indigenous land management, see the following sources that I consulted for my research on this walk!

BRIT Ethnobotanical Database - a website where you can search for any plant and see documented ethnobotanical uses.

Iwígara - a book describing cultural uses of various plants across North America

Tending the Wild - a book discussing native american land management in California

And feel free to make a google search about any plant you’re interested in. Unfortunately knowledge of many cultural uses have been stolen and were never recorded on paper when indigenous people were outlawed from speaking their native tongue. However, there is a lot of information out there, and I encourage you to go look for it!

At the end of the day, the participants walked away with a head full of knowledge and fresh perspectives about the landscapes they reside on and around.

Hikers return to the trailhead, contemplating the vast uses for our native plants. - PC: Rianna Shiree.

25th Anniversary Newsletter

Hiking With Your Dog in the Monument

Dogs are great! They make wonderful companions and hiking buddies, but it’s important to have some guidelines to help all have a safe, fun adventure. On Sunday, July 28th, Friends of Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument embarked on a special, dog-friendly hike.

In the Monument, summer wildlife abounded, including pollinators, resilient wildflowers, and energetic songbirds. We even ran across other animals enjoying the trail with their humans when we met some horses! Our hike along the PCT to Little Hyatt Lake culminated in some fun water-time for the pups to cool off, in a designated swimming area or course.

Rangers Nora and Emily went over Leave-No-Trace Principles from the Center of Outdoor Ethics (lnt.org) and applied those same ideas into a set of guidelines for dog and nature enthusiasts in the Monument. Below is what our group came up with, through conversation and in following Leave-No-Trace principles from the Center for Outdoor Ethics (lnt.org). Can you think of any other suggestions?

We also discussed some possible interactions to avoid while hiking with your dog. As safety is our priority, we discussed some native plants we were sure to encounter that can be toxic to pets, such as the Oregon Grape. Mindful enjoyment and appreciation of the natural world is something we at FCSNM strongly encourage, while remembering that sharing is caring, and time and place are everything!

Summer Nature Journaling

By: Isabel Jalamov

Have you ever captured the essence of a flower in your sketchbook or recorded the dance of a butterfly in the margins of your journal? Last week, I had the pleasure of leading a nature journaling workshop at the Green Springs Mountain Loop Trail in the breathtaking CSNM, where a group of eager participants and I immersed ourselves in the natural beauty of this unique landscape.

Planning this workshop was an adventure in itself. The Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, with its rich biodiversity and stunning vistas, was the perfect setting. I gathered all the necessary materials: sketchbooks, pencils, and field guides, and prepared a series of activities designed to engage both beginners and experienced journalers.

We began our day by spending some time orienting to the space and priming our brains to be mindful and observant throughout the day. Then, we dove into the art of nature journaling. We discussed the basics of the practice, its benefits, and practical tips for getting started. Our group, a mix of solo explorers and seasoned journalers, eagerly dived into the initial exercises. We started with simple observational sketches of nearby plants, rocks, and other things that caught our eyes, focusing on making meaningful observations.

After hiking a short stretch of the trail, we did an activity called “My Secret Plant”. Participants had to test their observation skills by creating an accurate journal entry which captures the essence of the plant they chose, in such a way that someone with no frame of reference could pick out the plant out of a small group of samples.

Lunch provided a welcome break and an opportunity for participants to relax, eat, and socialize. Many took this time to share their morning journal entries and continue looking for nature’s treasures, fostering a sense of community and mutual appreciation for each other’s work.

The afternoon brought with it a continued fervor to explore and note observations of interest. The first activity of the afternoon, known as “Zoom In, Zoom Out”, allowed us to think about and discuss the concept of scale. It was during this time I found that participants really began to form strong connections with the natural items they chose, and getting to know them on a deeper, almost personal level.

Our day came to a close with one final journaling activity. Participants chose to create field guides in their journals, classifying different species of lichen based on visual and tactile observations. The depth of observation and reflection in these entries was impressive.

As we wrapped up the session, we collected feedback from participants and provided information on further resources and potential future sessions. The positive feedback and expressions of gratitude were heartwarming. It was clear that this experience had made an impact on everyone involved. I am grateful to all the participants for their enthusiasm, creativity, and willingness to connect deeply with nature. This session was a beautiful reminder of the power of nature journaling to inspire, educate, and bring people together. It is my hope to continue to be involved in programs like this in the future.

Lost Creek Falls - Exploring Decomposers & Insects

By: Nora Tanel

On Sunday, June 30th, 14 people met at the Rite Aid in Ashland to go to the famous Lost Creek Falls. After figuring out carpools, we took Dead Indian Memorial road, turning left onto Shale City Road. The lack of information on how to get to the trailhead is one of the reasons for Lost Creek Falls’ notoriety. Luckily the whole entourage arrived in one piece.

The main emphasis of the hike was on insects. Specifically, we focused on decomposers, which is basically anything that you would find under a log. However, slowly our attention shifted to pointing out any insects that were found along the way. We were even able to use Loupes to get a closer look at some of the creatures we found.

Photo credit: Val Rogers

While it is only about three quarters of a mile to get to the falls, we did need to cross the creek a few times. There was still a variety of wildflowers in bloom including western columbine and Oregon sunshine. A full list of all flowers and butterflies that were seen on the trail can be found at the end of this post. We were even able to spot many pollinators including a variable checkerspot butterfly as well as bumble bees. One of the best parts about this trail is the creek that the group followed the whole way. The gurgling creek paired with the sound of song birds proved magical. It was a great opportunity to show the importance of water to all different types of life.

One of the insects that we saw most often is the Spittle Bug. It is known for its frothy, spit-like liquid that they produce when feeding on plants. They were often found on the thicker stems of grasses. Once we arrived at the falls, we all took a moment to be in awe of its beauty. Using binoculars we were also able to spot a fully grown salamander at the bottom of the falls, about seven inches long! The group stopped here to rest and eat some food while we talked about the designation and the history of the Cascade- Siskiyou National Monument as well as everyone's experiences in the Monument thus far.

After refueling, a small group decided to adventure out to an overlook on top of the bluff to hopefully catch a glimpse of Lost lake. It is the only naturally made lake in the Monumen that was formed when Lost Creek was cut off from the falls by a landslide.

It was a wonderful, quick morning hike. Everyone had a noteworthy time, filled with looking under rocks and investigating various flora. Certainly, it would have been difficult to think of a better way to spend the morning than exploring this special corner of the Monument.

List of Plants

Blue Dicks (Dichelostemma capitatum)

Yarrow (Achillea)

Pacific Trillium (Trillium ovatum)

Jacob’s Ladder (Polemonium occidentale)

Western White Anenome (Pulsatilla occidentalis)

Orange Honeysuckle (Lonicera ciliosa)

Oregon Checkermallow (Sidalcea oregonia)

Giant Red Indian Paint Brush (Castileja miniata)

White Inside Out Flower (Vancouveria hexandra)

Slender Cinquefoil (Potentilla gracilis)

Common Wooly Sunflower (Eriophyllum lanataum)

Creeping Buttercup (Ranunculus repens)

Columbian Windflower (Anemonastrum deltoideum)

Deerbrush Ceanothus (Ceanothus integerrimus)

Washington Lily (Lillium washitonianum)

Arrowleaf Buckwheat (Erigonum compositum)

Harvest Brodiaea (Brodiaea elegans)

Cascade Oregon Grape (Berberis nervosa)

Bride’s Bonnet (Clintonia utifloria)

Three Leaf Foamflower (Tiarella trifoliata)

Creeping Snowberry (Symphoicarpus malus)

Common Cowparsnip (Hercaleum maximum)

Columbian Tiger Lily (Lilium columbianum)

Diamond Clarkia (Clarkia rhomboidea)

Candy Flower (Claytonia siberica)

List of Butterflies

Variable Checkerspot

Silvery Blue

Cedar Hairstreak

Thicket Hairstreak

Aquatic Habitats & Species of the Monument

Information in this blog post is from the presentation put on for the Friends of Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument by BLM Fish Biologist, Chris Volpe.

By: Zaynab Brown

If you have been following our organization for any length of time, you probably know that we are really into beavers. Beavers do amazing things for the landscape and those who live in it, including humans. You may have also heard the word “riparian” thrown around. In ecology, riparian is defined as relating to wetlands adjacent to rivers and streams. While we have touted the benefits of healthy riparian areas, it’s time that we learn more about the streams themselves. Who lives in these, sometimes ephemeral, waters and in what unique ways are they being impacted by changes to our climate and waterways? To answer these questions, the Friends recruited one of the best people for the job: Chris Volpe.

Chris Volpe is the Medford District and Ashland Field Office Fish Biologist. He has been with the BLM for 22 years and spent another four years prior to that in the Rogue Basin collecting fish and habitat data with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Chris has been involved with monitoring, research, and restoration of aquatic species and habitats in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument for most of his career.

On Friday, June 14th, Chris and a room full of the aquatically curious gathered to gain a better understanding of the aquatic habitats and species of the Monument. This starts with understanding that, within the Monument, there are 724 miles of streams, 57 of which are fish-bearing! Of course, not all streams are flowing all year. Those streams are called “intermittent streams” and make up the majority at 455 miles compared to 268 miles of “perennial streams”, or streams that flow year-round. However, even intermittent streams provide important habitat, including for fish. Springs are also a type of free-flowing aquatic habitat that contribute high-quality water to the larger streams and provide unique habitat.

Not all aquatic habitat in the Monument is free flowing. You can also find 790 acres of ponded and slow water habitat. While most of this acreage is represented by large reservoirs such as Hyatt and Little Hyatt Lakes, there are also ponds and fens. Fens are rare, peat-accumulating wetlands associated with springs and are found in a couple locations within the Monument.

It is of no surprise, considering that the Monument was designated for its incredible biodiversity, that this diversity extends to its aquatic inhabitants. There currently are seven native fish species found within the Monument, amphibians including the Pacific Giant Salamander and threatened Oregon Spotted Frog, Western Pond Turtles, mammals such as beavers and river otters, as well as many species of mollusk and macroinvertebrates. The native fish include Speckled Dace, Tui Chub, Sculpin, Cutthroat trout, Redband trout (a subspecies of the rainbow trout), Jenny Creek Suckers, and migratory steelhead. Though this diversity may soon see an increase due to one of the biggest changes to the watersheds of southern Oregon and Northern California that has happened in quite some time.

If you have been following local news, you have most surely heard of the successful campaign to remove the dams on the Klamath River. This momentous accomplishment will have ripple effects on aquatic ecosystems far and wide, including in the Monument. A big winner may be the migratory fish species. Jenny Creek, which is part of the Klamath River Watershed, may now be colonized by both Steelhead and serve as a place for Chinook Salmon to spawn and rear. The future may also see Pacific Lamprey and Coho Salmon make a return. However, natural barriers like Jenny Creek Falls will still limit the extent that fish will be able to colonize streams within the Monument.

On Saturday, June 15th, participants got an opportunity to experience the aquatic life in Jenny Creek first-hand. It was a beautiful day as we watched Chris and Jenna Volpe don waders and a backpack that looked like it would sooner be found on the set of GhostBusters than a wild and scenic waterway. Yet this piece of retro-looking technology would allow us a rare peek at what lived below the water’s surface.

We stopped at a section of Jenny Creek where beaver dam analogues (BDAs) had successfully slowed and spread the water into a wide and murky pool. Chris jumped in, metal rod in one hand and net in the other, as he and Jenna methodically made their way slowly through the pool while releasing small amounts of electricity intended to stun any fish or amphibians in the vicinity, making them easier to catch. This method, called electrofishing, soon turned up results as Chris gently placed several specimens into a bucket containing water that Jenna was carrying.

Once back up on dry land, Chris carefully lifted out a small Redband Trout. Its silver scales and distinctive pattern glistened in the daylight. It was easy to picture it flitting through the water, glinting as it passed through dappled shade cast on the surface. Next, Chris lifted out the other star of the show: an adult Jenny Creek Sucker.

Jenny Creek Suckers are a unique “dwarfed” population of Klamath Small-scale Sucker, endemic only to Jenny Creek. This is due to the population's isolation from other suckers by Jenny Creek Falls, a complete fish passage barrier to upstream migration. It was easy to see how the sucker was suited for life sifting through the bottoms of streams in search of algae with its dull brown color and muted appearance. Chris remarked that fish surveys this year had revealed an uncommon abundance of Jenny Creek Suckers, particularly juveniles. He speculated that it was due to an unusual high flow event in the creeks and streams this spring resulting in the reduction of the population of macroinvertebrates that also feed on the algae, allowing more food for the new generation of fish.

The next stop for the group was lunch at a nearby pond. This pond, the result of restoration work by the BLM in 2019 to excavate a historic pond that had been filled in by natural processes. The pond was then soon colonized by the Western Pond Turtle, a species that may soon be listed under the Endangered Species Act, and beavers whose lodge could be seen rising from the middle of the pond. As participants took their lunch, we all waited quietly, hoping to see a turtle pull itself out onto one of the many floating logs to bask in the afternoon sun. The turtles, notorious for their shyness and sensitivity to vibrations, remained elusive until someone spotted one out near the middle of the pond where it probably assumed our clumsy footsteps made us poor swimmers. Binoculars were passed around as we all got a chance to see the surprisingly large reptile.

However, with nearly all stories of ecosystems in the present day, there seem to be existential threats around every corner. This is also true for the aquatic ecosystems of the Monument. The fact is that fish, and other aquatic species, need water to survive. Major diversions transfer water from the Klamath Watershed to the Rogue Basin Watershed to increase irrigation for the Valley below. This results in significant reduction in the flow in lower Jenny Creek, as well as other creeks and streams in the Monument, often during the lowest-flow time of the year. Infrastructure that allows these kinds of diversions, such as dams, also often results in the complete aquatic organism passage barriers. Degraded water channels also become more efficient at moving water away from the landscape instead of storing it in flood plains and as ground water. This degradation is associated with many things including the removal of beavers, cattle grazing, reduced riparian vegetation, and roads, culverts, and ditches.

Of course, you cannot discuss water without acknowledging the role of long-term drought in reducing the overall amount of precipitation falling on the landscape each year. Many streams that were once considered perennial several decades ago are now intermittent and dry up most years. This reduces the available habitat for aquatic organisms.

Like most problems that are largely due to human activity, solving it also relies on the actions of humans. This includes process-based restoration, such as adding large wood/rootwads to waterways, low-tech process-based restoration such as beaver dam analogues and post-assist log structures (PALS), and the reintroduction of beavers onto the landscape. It is also important to consistently take inventory to determine the “what, where and how” of existing ecosystems processes and then monitor to evaluate the efficacy of restoration efforts. An citizen-science example of both of these is the recent Beaver Scavenger Hunt put on by the Friends to determine where beavers are currently in the Monument and what they are doing. The BLM also carries out work such as monitoring water quality and quantity and populations of aquatic organisms.

It can be too easy for land-loving humans to overlook the fascinating aquatic habitats and species. Yet these habitats often form the foundation of many important ecosystems in the Monument. While there is a very long road ahead to restore the majority of the waterways to healthy states, proven progress has been observed using the restoration strategies mentioned above. It now requires consistency of efforts from both the private and public spheres to emulate and restore the natural processes through funding and hands-on work.

If you would like more information and to get involved in aquatic and riparian restoration taking place in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument and surrounding area, please sign up for our newsletter and check out some of the work being done by other local non-profit organizations below.

Project Beaver: https://projectbeaver.org/beavers

Vesper Meadow: https://www.vespermeadow.org/vesper-meadow-preserve

2024 Nature Camp Monument Days Kick-Off

By Emily Cochran

The first Monument Day was a success! On Wednesday, June 19, students from The Crest Nature Camp at Willow-Witt Ranch visited the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument for a day of sun and fun! Thirty-two students, ranging in ages from 6 to 11 years, trekked through fields of wildflowers and lush conifer forests.

Rangers Nora and Emily led hikes up Hobart Bluff, with great views of the Cascade and Siskiyou Mountains as well as the Klamath Basin and Rogue Valley. From the peak were great vistas of Pilot Rock and Soda Mountain Wilderness within the CSNM. Along the way, students made use of their nature journals to connect more deeply to nature. Great places to stop and take in their environment provided opportunities for mindfulness and connection.

We also explored the trail as naturalists, learning about the different habitats and tree species. We began through natural stands of white fir and Ponderosa pine, with more whimsical white and black oaks as we got lower in elevation and neared riparian areas. Above the tree line the aspect changed; we were now in the western extent of the Great Basin. Students studied juniper and sagebrush foreign to most of the valley. At the summit we enjoyed a feast for our hungry bellies and an eagle-eye view.

On the descent, we enjoyed trail games such as color matching since our ecosystem is nature’s canvas. Especially plentiful were the wildflowers. There were beautiful scenes of greens, reds and blues. We even passed a lovely slope full of the yellow Oregon Sunshine. Of course, with all the flowers, pollinators were a plenty. Grasshoppers, beetles, and butterflies, oh my!

After our hike, students participated in arts & crafts to flex their creative muscles. They made dragonfly pins from various household items. As a mixed age group, we helped each other make a buzzing menagerie of dragonflies. All in all, a really enjoyable day to spend in the summer. 😊

Beaver Scavenger Hunt

By Zaynab Brown

On Saturday, June 1st, 2024 almost 50 volunteers converged at Pinehurst School in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. This nature-loving group, made up of students, professionals, and retirees aged 19 - 80 years, was there for one purpose: to look for signs of beavers.

While Oregon might be considered the Beaver State, beavers are conspicuously absent in many of our local waterways, including the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Waterways under beaver management not only create vibrant and healthy habitats for wildlife, but result in improved water quality and quantity, better climate resilience, and wildfire protection for humans. However, as is the case with many broken things, the process of destroying it is often easier than putting it back together. The same can be said for getting beavers back into the Monument.

Despite the Monument supporting a vibrant beaver population for millennia, rampant trapping for economic gain by European colonists severely decimated their population throughout the American West. As time passed and harvesting beaver pelts no longer provided financial incentive, different pressures moved in to make re-establishment a challenge. These challenges include conflict with humans over agriculture, ornamental landscaping, and infrastructure such as roads, ditches and culverts, as well as water diversion for irrigation and hunting and trapping for sport.

As with every challenge though, there are people and organizations willing to meet it head-on. One of these organizations in Southern Oregon is Project Beaver, a nonprofit that works to nourish a world where humans partner with beavers for the resilience of our planet. Led by their executive director, Jakob Shockey, Project Beaver with input from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) created the Beaver Management Plan for the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. In the plan, a strategy is laid out for attracting and retaining beavers in the landscape through the use of riparian restoration techniques. In order to most effectively focus restoration efforts, it is important to have an accurate baseline for where beavers are (and where they are not) and what they are currently doing. This is where the Friends of Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument and the Beaver Scavenger Hunt came in.

From Pinehurst School, we organized small teams of 3-5 people dispersed to pre-selected sites chosen for historic and present beaver habitat suitability. Armed with data collection tools, they searched approximately 12 miles of waterways through dense vegetation, precarious slopes, and uneven ground. Walking along a riparian corridor is very different from an established trail. While many aspects are more difficult, such as bushwacking and dealing with deep, incised streambeds, the benefits are an unparalleled view of the wildness of the Monument. As Jakob Shockey said “Rarely do grown-ups have an excuse to spend all day playing in the water looking for beaver sticks, let alone 50 of them.”

Once everyone returned to Pinehurst in the afternoon, tired but refreshed by the beautiful weather and sense of accomplishment, we all gathered around to hear the discoveries that each group made. Building on previous riparian restoration efforts, including the installation of beaver dam analogs, teams reported fresh beaver signs in several key locations. In fact, some teams found so much sign that they were unable to complete their entire route as chewed sticks and stumps emerged from every bend in the creek. While this was not the case with every group, all reported on the beautiful forests and meadows they happened across including impressive old growth trees in some locations as they ventured off the beaten path.

The data collected was sent to Project Beaver where it is being reviewed and will directly impact future collaborative and process-based restoration to put beavers in charge of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument’s waterways once again. While it was heartening to find fresh sign, there is still a long way to go as the number of beavers in the Monument pales in comparison to what is needed to revive our riparian areas and reap their benefits. There has been recent legislative progress to protect beavers in Oregon, but it is still legal to hunt and trap them within Monument boundaries. The Beaver Scavenger Hunt is just step one in a long-term, collaborative effort to help beavers do what they do best to the benefit of us all.

While the Beaver Scavenger Hunt was a huge success, that still leaves the question of what is next. We at the Friends are continuing to center the stewardship of our riparian areas as we look toward the future and the implementation of projects to make the Monument a refuge for beavers and all the biodiverse creatures that call it home. We will continue to collaborate with other organizations taking part in process-based restoration projects and carrying out the Beaver Management Plan. Stay tuned for more adventures in the Monument to look for the fruits of our labor –and maybe a chance to play in the water!

Plumbing the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument

By: Zaynab Brown

Mark Twain is famous for saying “Whiskey is for drinking and water is for fighting over” and that couldn’t be more true than it is in the present moment, especially in the Western United States. What started during European settlement as a feeling that the vast amount of water in the west could never be depleted has transformed into a point of tension and anxiety. Our need for water increases year after year while climate change simultaneously upends our norms while the Earth grows hotter. Predictably, humans react by trying to bend nature to our needs. In Oregon and California, and around the world for that matter, this manifests itself in epic engineering feats to dam mighty rivers and divert their water to irrigate millions of acres of otherwise dry farmland and to provide drinking water and fill swimming pools in growing suburban enclaves. This trend is also true for the waterways within the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument.

All throughout the Monument you can observe evidence of the “plumbing” so ubiquitous in the west. Various dams and reservoirs –such as Howard Prairie Reservoir, Hyatt Reservoir, Keene Creek Reservoir, and Little Hyatt Reservoir– throw splashes of human-augmented blue over the landscape. While they may provide recreational opportunities, meadows that were once wet grow parched in the summer and streams can no longer support beaver dams with their reduced flows. Now, more than ever, everything comes at a cost.

Most of the water that flows through the creeks and streams of the Monument originates from springs and snow melt. However, much of that water is diverted before it can reach its historic destinations and ends up in the Talent Irrigation District (TID) system that provides irrigation water to a large part of the Rogue Valley to the tune of billions of gallons per year. In fact, water that flows in Keene Creek would naturally flow into the Klamath River watershed. However, a diversion results in that water jumping watersheds into the Rogue River watershed instead. In light of the dam removals underway on the Klamath River, it is unlikely that this diversion will remain uncontested into the future.

On Friday evening, April 26, John Schuyler, a retired forester, gave us a broad view of the history of water policies and infrastructure in the West to inform our understanding of the current situation in Southern Oregon and Northern California. From the Hetch Hetchy reservoir to the Hoover Dam, the theme of human hubris clashing with the reality of water scarcity was found throughout. On Saturday, when a group of participants ventured out into the Monument to see this “plumbing” in person, the irony couldn’t be ignored as we walked along the PCT adjacent to Hyatt Lake. The Monument, designated for its incredible biodiversity and wild character, could not escape the pervasive touch of humans intent on extracting its resources via concrete dams and channels that conveyed cool, clear water into ditches irrigating greener pastures down below.

2024 Monument Research Symposium

By: Zaynab Brown

Every year, the Friends of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument is delighted to award a number of grants to undergraduate and graduate students and Indigenous Americans for faculty-supervised research projects that enhance the understanding, appreciation, preservation and/or protection of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. These research projects can, and have, taken many forms including in the realms of biology, environmental sciences/education, sociology, arts, humanities, and business.

An essential component of receiving this grant is the presentation of the students’ research at our annual Monument Research Symposium. This research represents many hours spent in our beautiful Monument gathering data and then countless more analyzing it. To ask our three grant recipients from 2023 to distill all of their findings into a 20 minute presentation is no small feat, but they delivered with flying colors.

Our first presenter, Trevor Holt, is a senior biology major at Southern Oregon University. He worked with his advisor, Dr. Jacob Youngblood, to catalog grasshopper species found in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument and pilot a long-term monitoring program. Both of these objectives were designed to better understand grasshopper biodiversity in the Monument in the face of climate change and human development. Monitoring grasshoppers is important because they are a keystone species, the most abundant grassland herbivore, and comprise a diverse biology in many diverse habitats. When it comes to climate change in particular, we learned that grasshoppers can be an important indicator species due to the fact that all of their life stages are dependent on temperature, from hatching to feeding, movement, and population growth. With that in mind, some grasshoppers are more adept and hardy while others, such as the endemic Siskiyou slant-faced grasshopper (Chloealtis aspasma) is more vulnerable to change and to the threat of becoming isolated. With over 2000 individuals collected and identified, Trevor proved what many would have suspected: The Monument is rich in grasshopper biodiversity with over 17 species found in his study! As the monitoring program continues into the future, Dr. Youngblood and his team hope to monitor at lower elevations and analyze the relationship between populations and weather.

Grasshoppers (and a spider!) perched on the edge of a collection net.

Photo by Trevor Holt

Our next presenter, Tayla Moore, used her Monument Research Grant to focus on a single grasshopper species, the aforementioned Chloealtis aspasma. Tayla is also a senior biology major at Southern Oregon University who worked with her advisor, Dr. Jacob Youngblood to map the distribution of C. aspasma and uncover its natural history. C. aspasma, as mentioned above, is also called the Siskiyou slant-faced grasshopper. While Chloealtis species are widespread in North America, C. aspasma is endemic to Southern Oregon and potentially Northern California where they are designated as a species of concern by the Bureau of Land Management and United States Forest Service. They live in open fields and meadows at high elevations and their dispersal is limited by smaller wings and their preference for high elevation, mountainous regions. In total, Tayla was able to visit 26 sites within the Monument and found C. aspasma in ten. Of these ten, five were previously undocumented populations. Unfortunately, observing this elusive grasshopper’s natural history proved to be more difficult and further research will need to be done to uncover more information on its feeding, reproduction, and thermoregulation patterns.

Chloealtis aspasma

Photo and annotations by Tayla Moore

Finally, our third presenter, Hilary Rose Dawson, a Ph.D. candidate from the University of Oregon, joined us for a second year in a row to explore truffle species found in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Now, most people’s experience with truffles begins and ends in a culinary context, and while there are certainly a handful of culinary truffles found in Oregon, we also learned about the fascinating diversity of non-culinary truffles found just below the surface. These truffles have scents ranging from artificial banana to burnt rubber and serve a variety of essential ecological functions. However, humans aren’t exactly known for their sensitive noses so it was essential for Hilary –aided by her sister, Heather Dawson–to employ a canine friend named Rye. In 2023, they visited almost 30 sites in the Monument and found 57 species across 26 genera, an incredibly diverse range! Of these, 32 were not documented in genetic databases making them potentially undescribed species. Hilary hopes to finish sequencing and finalizing the list of truffle species found in the Monument and ultimately publish a paper on the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument’s truffle diversity and a case study on how truffle dogs can be used in truffle research.

Heather Dawson photographs a Hysterangium truffle while Rye waits for her to throw the ball again. Photo by Hilary Rose Dawson

If you are interested in learning more about these projects, the symposium can be watched in its entirety on our YouTube channel at https://www.youtube.com/@friendsofthecascade-siskiy4103

With our 2024 Monument Research Symposium a resounding success, we are looking forward to getting to experience the unique projects that students will propose for this coming grant cycle. Applications are now open and information can be found at https://www.cascadesiskiyou.org/programs . The deadline for applications is April 26 at 11:59 PM PST.

Wildlife Tracking - 2024

By: Zaynab Brown

For most people, when we experience nature we experience it through the lens of a human. This is, of course, to be expected. However, in learning about wildlife tracking, you not only learn to differentiate between a feline and canine paw print but are also invited to see the world from the perspective of an animal. While the animal is absent, you get a snapshot into a moment of his/her life as he/she navigates the world. Maybe you observe that the animal is trotting and ask yourself “why?” or “where?” Why was it that the coyote decided to detour around the ravine and what did he find there? What did the trees look like from his perspective? Needless to say, we can’t know the true answers to these questions but in the process of considering them we may begin to look at the environment around us differently. We may notice things that before had seemed too small or insignificant to grab our attention. Suddenly, the world is much more fascinating.

To begin this fascinating journey into the world of animal tracking, we started in a classroom. Admittedly, this is less exciting than a forest floor or open plain but humans are strange creatures. Our instructor for the Friday lecture and Saturday hike was Nolan Richard, a biology teacher at South Medford High School who currently holds a Level 3 Track and Sign Certificate from Cybertracker International.

Together, in a group of almost thirty participants, we learned to identify paw prints belonging to cats, such as bobcats and cougars, and dogs such as coyotes and foxes. We examined the subtle differences in the orientation of their pads and the presence of claws. We saw large bear tracks and discussed the differences between elk and deer. We even learned how to use our own hands to determine the left and right orientation of what had initially appeared to be identical images. Together, we examined rubbery casts of prints and attempted to identify the animal who had made them. Some were from our area, such as the skunk, beaver, and mountain lion. Others however, like the massive grizzly bear, we were unlikely to see in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument (or in Oregon at all for that matter!)

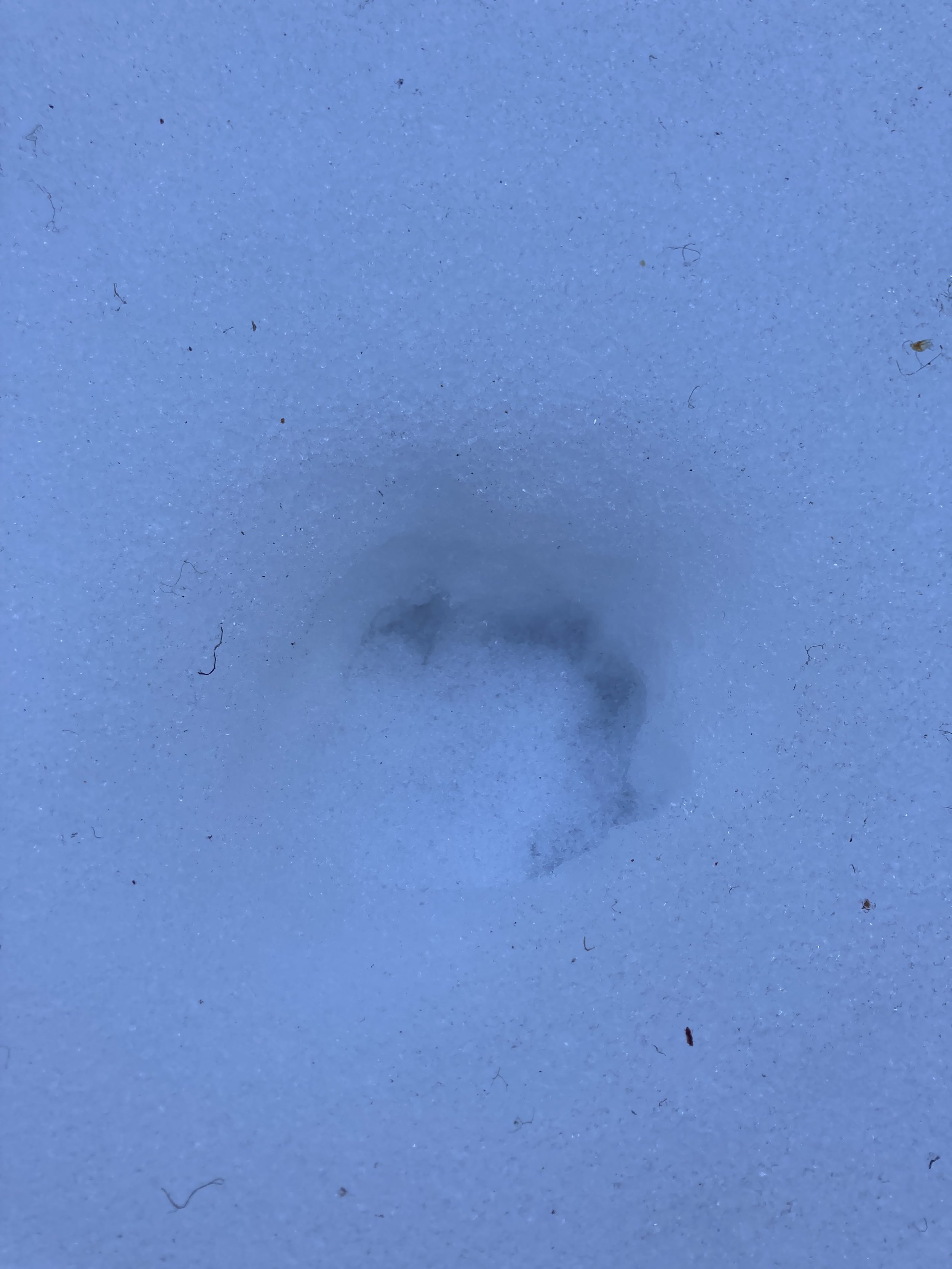

Rubber-like casts of prints. #11 is a grizzly bear.

Armed with this new knowledge, we met on Saturday excited to find some tracks and put our burgeoning skills to the test. Although we quickly learned that when it comes to tracking, some conditions are better than others. In a perfect world there would be powdery snow, not too deep and not too recently fallen. We don’t live in a perfect world however and the snow we had was icy and hard. While this will allow some larger animals to still leave tracks, most animals will simply walk on top of it without leaving a trace. But this didn’t stop us and soon we found coyote tracks snaking through a small meadow and many deer tracks. These prints, while not pristine, could still tell us a story if we looked closely enough.

An important thing to remember, especially when looking at tracks that lack fine detail, is to consider the environment around you coupled with knowledge about local species. Some species, while abundant at lower elevations –such as a skunk– are much less likely to be found at higher elevations. Or, if you are looking for snowshoe hare tracks, they are much more likely to be found around tree cover than out in the open.

Finally, it is not only tracks that animals leave behind! There is also a whole world of “animal signs.” Perhaps most well known of the animal signs is scat, or feces. Our group discovered lots of scat when we visited Buck Prairie Two. We learned to differentiate between smaller deer scat and larger, more irregularly shaped elk scat. The scat can also tell you a lot about the diet of the animal that left it. For example, a domestic dog that primarily eats processed food will have scat that is very uniform in texture while that of a similar-sized animal such as a coyote or bobcat will usually contain fur or bones. Our group also found squirrel middens –mounds of discarded douglas fir cone debris, elk rubs, old beaver chews, holes made by a pileated woodpecker, and lots of browse.

Near the end of our hike, we stumbled upon some of the most detailed tracks yet. Four clear toes with claws and a heel pad were starkly visible and the animal that made them was slowly plodding in a direct-register walk where the back foot directly replaced the front in the same print. Participants were suggesting a large coyote or maybe even a cougar! The answer turned out to be much more mundane. It was a domestic dog. According to Nolan, dog tracks are some of the most common you find, especially if you are at a location that humans frequent. Since domestic dogs range extensively in size and shape, it can be almost impossible to differentiate them from their wild counterparts. This is why, Nolan reminded us, that it is especially important to pay attention to your environment. Are there human boot prints nearby? Is it near a road? In these circumstances, always assume it’s a dog.

Dog or not, I couldn’t help but imagine the way the animal saw the world as it walked through the peaceful forest and left prints in the crunchy snow. Did he/she also notice the squirrel middens and smell the elk scat, or take note of the way the snow glittered in the afternoon sun? We’ll never know but we can imagine.

Meet the Monument at Public Lands

By: Zaynab Brown

One of the things I enjoy most about working for the Friends is getting to tell people about the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. As I explain its size (114,000 acres) and its proximity to Ashland, people’s eyes usually widen. We live in a valley surrounded by mountains and wild places, but we often take them for granted. The fact that some of that landscape is so biodiverse that it merited federal designation is even more of a surprising fact to some. While it is possible to describe rare and endemic species, eco regions, and mountain ranges, it’s not the same as getting to see it with your own eyes. So, when words fail me, as they often do, I will direct the curious to a very special video.

At just over 17 minutes long, it may initially seem short for a documentary. But contained within those minutes is an incredible cinematic and photographic journey of the Monument and the creatures who call it home. Sweeping drone footage is coupled with captivating shots of some of the smallest Monument inhabitants. Combined with insightful narration by Crystal Nichols, the filmmaker, it transports you to another world in our own backyard that is open to all of us to explore responsibly. Therefore, it was an easy decision to base an event called Meet the Monument around Crystal’s film.

At Public Lands, an outdoor recreation and gear store based in Medford with whom we collaborated, a group of around thirty participants gathered on a Thursday evening.The crowd was made up of both Monument lovers and those who had never even heard of it. With snacks and drinks provided by the store, the film was played to a keen audience. Afterwards, Crystal took the stage, so to speak, and among the displays of jackets and ski goggles answered questions about her process of creating the film and the many adventures she had getting those perfect shots. Collette, Executive Director of the FCSNM, then shared a brief presentation on our organization and resources for exploring the Monument and getting involved.

The film itself was partially funded by the Friends Research Fund which awards small grants to university students and indigenous people that enhance the understanding, appreciation, preservation, and/or protection of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Crystal’s film certainly did just that.

If you or someone you know is interested in applying for the 2024 grant cycle of the Friends Research Fund, the application will be opening soon and can be found under the Student Research Grants section of our website.

Exploring Conifer and Shrub Diversity on the PCT Trail with Naturalist Nolan Richard

Starting in Ashland, the day was gloomy. Rain thudded down through gray skies and the chilly air nipped at our hands. Our group had high hopes the rain would become snow at the higher elevation of our destination, a section of the PCT off of old highway 99 toward Pilot Rock. As we piled into the cars and took off, we found that slowly, the rain dissipated and sun broke through the clouds to illuminate the fresh snow along the roadside.

Our guide and teacher for the day, Nolan Richard, a local naturalist and seasoned biology teacher, embarked on an introduction to the world of conifers and shrubs. Nolan, with a decade-long devotion to studying native plants along the West Coast, has shared his expertise in the past by teaching classes for the Native Plant Society. His deep interest in Plant Biogeography—understanding the distribution of plant species and communities—propelled our adventure.

The trees encircled us, prompting Nolan to engage us in identifying the varying conifer species that thrived in this environment. Brushing snow off a couple of saplings, Nolan showcased how to inspect needles to discern between the Grand Fir and the White Fir. As a group, we gathered around, following Nolan's techniques to identify a White Fir displaying hybridization traits and a Grand Fir with minimal signs of hybridization.

Our journey led us to a halt in an area teeming with a dense understory. The shrubbery, devoid of leaves and bereft of vibrant colors, posed a challenge in identification during its dormant phase. Nolan assured us that although daunting, it wasn't impossible. With his guidance, the group keenly observed nuances in branch sizes, textures, and growth formations. Soon, we triumphantly identified snowberry, serviceberry, oregon grape, and several other shrub species amidst the subdued winter landscape.

Nolan often emphasized the importance of identifying conifers and understanding their environmental placement by asking, 'Why are they growing here?' In the end, our hike under Nolan's tutelage was not merely a stroll but an enlightening journey through the diverse world of conifers and shrubs.

Fire History & Ecology of the Monument

By: Zaynab Brown

To watch a recording of Rich’s lecture click HERE

Living in Southern Oregon or Northern California, it is impossible to ignore the reality of fire. In particular, the raging forest fires that blanket the valley floor in a thick, acrid layer of smoke that obscures the mountains and turns the sun red. Each year when the moisture of springs starts to give way to crisp undergrowth and fire season begins, a sense of anxiety informs almost every day; what is going to burn next? It is true that our local ecosystems rely on fire for health and productivity, a fact that the indigenous people have known and used to their advantage for countless generations, yet are these huge, destructive fires the norm? If not, how can we change our approach to fire to work with nature instead of against it? These and other questions are what Rick Fairbanks set out to address in our Fire History and Ecology Hike and Learn.

Rich Fairbanks has accumulated a wealth of knowledge and interesting stories through his career with the U.S. Forest Service for 32 years in fire management, planning, and silviculture. He is informed by his degree in forestry, his work on the Biscuit Fire Recovery Project, and his experience at his own property where he does a considerable amount of underburning in the mixed conifer forest. It was with his classic dynamism and humor that Rich began to take us through the multi-dimensional picture of fire in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument.

It isn’t possible to discuss the ecology of something without considering the plants. When it comes to fire ecology in particular, it is truly the plants that tell the story of an ecosystem that coevolved alongside this force of nature and has the adaptations to prove it. While there are many herbaceous species that also benefit from being burned, we primarily focused our attention on trees. We appreciated the robust fire resistance of the ubiquitous ponderosa pine with its thick bark, self pruning habit, and robust wound response. Other conifers such as the douglas fir, sugar pine, and incense cedar, while not quite as impressive as the ponderosa, still sported fire resistant bark and the ability to easily withstand a low-severity fire. However, fire resistance is not confined just to conifers. Oak trees also wield adaptations to fire in the thick bark of older trees, the ability to resprout from stumps, and how acorns stored in the duff are stimulated to sprout and grow. If you are interested in learning more about the Monument’s oaks, please visit our previous blog post: Oak Trees in the Monument

When the indigenous people first arrived in the region of the present-day Monument, they were faced with an environment that already had intense fire activity. That left them with a choice: React to fires started by lightning or work with this natural phenomenon and pick up the torch. They chose to make friends with fire and learned how to predict and wield it to manage the landscape. When European colonists arrived in the area, they did not recognize the important role and invaluable knowledge of the indigenous people in the management of the landscapes that they took for granted. This led to a period of fire suppression that we still experience today where smaller, low severity fires are not allowed to burn and huge, high severity fires are now ripping through the dense vegetation spurred on by hotter and drier summers.

Rich took us on a tour of the science behind wildfires and what causes their behavior including fuels, weather, and topography. Ultimately, the only factor that humans can influence is fuels. It was from there that we learned about fuel categories and how the surface area to volume ratio affects how materials burn. Finally, Rich discussed what he hopes will be the future of fire in the Monument. In his opinion, this future includes a lot more planned fire, mechanical fuel treatment when appropriate, the effective management of noxious weeds, more fire research, and greater support for Minimum Impact Suppression Techniques (MIST).

We were fortunate to have many attendees in the audience who brought their own experience with fire and botany to the table. Questions ranged from adaptive phenotypes of local douglas fir to the importance and power of community engagement in how fire is managed in our public lands. In particular, we discussed the importance of MIST in preserving the character and value of wild places that would otherwise be damaged due to heavy-handed suppression techniques.

It was with enthusiasm that we all gathered at the trailhead to the Green Springs Mountain Loop trail in the Monument the next day. Despite the discussion of the possibility of snow, the weather could not have been more beautiful. Warm sun shone down and made us a little too warm for our winter jackets and the shade had just enough chill to keep us on our toes. With an impressive group of 17 people, we began to snake our way down the trail. Rich, who helmed our educational adventure, stopped us along the way to quiz us on conifer identification and to admire old-growth Douglas firs casting cool shadows from above.

As we walked along the relatively popular trail, we were stopped just as frequently by participants who had insightful questions or spotted plants that they wanted to share with the group. It made for slow going, but often the best hikes are the ones that meander and pause frequently to notice the little things.

We emerged from the trees and found ourselves gazing out at an incredible vista looking down into a valley. The golden meadow stretched into the horizon before giving way to mighty blue mountains. It is here that we turned right and crossed through a grove of oak trees, arranged in a “fairy ring.” Rich stopped to tell us that this was a tell-tale sign of fire where an oak had been burned and then resprouted around the trunk. Most likely, if you were to look carefully, you could find charred bits of oak in the center. But this was not our final destination. Soon, we found the real goal of our detour: A fire refugia.

Fire refugia are unique places that are protected from high severity fire by topography, microclimate or fuel conditions and allow individual trees to reach a very old age. The centerpiece of this particular refugia were towering ponderosa pines and douglas firs. As we approached, their true age and size were humbling. People often make pilgrimages to the redwoods to witness trees that evoke a sense of wonder, but we had our very own in the Monument. Neon green lichen clung to their trunks and their thick and gnarled bark told a story of past fires that charred but did not kill. Blackened fire scars crawled up their sides.

We had the honor of eating our lunch below the soaring trees as their branches cast shade like they had for hundreds of years. Due to a random quirk in the landscape, we were able to experience a miniscule slice of what the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument may have looked like hundreds of years ago when people and fire were able to work together.

Creating Cascade-Siskiyou Beaverhoods with Vesper Meadow

By: Zaynab Brown

As the saying goes “Even the best laid plans often go awry.” This was the case on Saturday morning when residents of the Rogue Valley woke up to find fall gardens covered in frost. While I was sad to see the end of my tomato plants, the more pressing concern was the day of stewardship the Friends of Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument (FCSNM) had planned in collaboration with Vesper Meadow. A day of wading into a creek wielding shovels and loppers was suddenly less appealing when it felt more appropriate to be wearing a warm hat and mittens.

The event, called Creating Cascade-Siskiyou Beaverhoods, was to be a day of “behaving like beavers” as volunteers toured along Latgawa and Spencer Creek on Vesper Meadow property and Monument lands to see and tend to the beaver-based restoration projects that were put in place over the last couple of years. Not only would participants get to learn about low-tech, process-based restoration strategies, they would also get a chance to get their feet wet, so to speak. However, with the prospect of those feet also getting frozen, the tough call was made to cancel.

Yet, all was not lost. For those intrepid participants who were up for the challenge of a hike with some snow on the ground, we met at Buck Prairie II at 1:00 PM. There, Stasie Maxwell, FCSNM board member and Indigenous Partnership Programs Manager at Vesper Meadow, led us along Spencer Creek as it passed through the Monument and Vesper Meadow property. There, we were able to observe past structures made from local, natural materials meant to span the creek channel, slowing and spreading the water. We also saw past sloping of the creek bank. As we snaked through the trees, frozen mushrooms peaked out of the snow like time capsules from the last heavy rain.

Even though our purpose had shifted and the size of our group reduced, the afternoon was filled with insightful questions and joyful curiosity. Zaynab Brown, Program Coordinator for FCSNM, and Stasie painted a picture of a partnership that would further the creation of a landscape that could once again support beavers, the true stewards of our waterways.

A Successful 2023 Annual Celebration

It is a strange feeling, to work for so many hours, days, weeks, and months on something and then have it be over in the blink of an eye. However, that bittersweet feeling is balanced by the joy of witnessing the community coming together. Volunteers were at their stations, the decorations were beautiful, and we could smell the delicious aromas wafting over from where the caterers were setting up. We found ourselves taking a moment to pause and be in awe of the beautiful weather we had, of the still air that barely caused the tablecloths to flutter.

We knew that having our Annual Celebration in the middle of October would be a gamble. Every day in the week leading up to October 15, Collette, executive director of the Friends, and I would anxiously check the forecast. We dreaded seeing a small, pixelated raincloud posted next to our chosen Sunday and our hopes dashed. Of course, we had a back up plan, but the Pinehurst School gym with its dim lighting and basketball hoops couldn’t hold a candle to an afternoon under blue skies and sunlight. So, as the clock ticked closer to 3:30 PM and the sun gently warmed our skin in t-shirts and summer dresses, we couldn’t believe how lucky we were.

On the lawn in front of the picturesque red school house of Pinehurst School, nestled in the heart of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, stretched a small sea of round tables under the shade of a grove of towering ponderosa pines. Each had a centerpiece crafted from pine cones, needles, and bright red berries collected from the local landscape by the fabulous, Mary Ann and assembled with care by volunteer extraordinaire, Cindy.

All around us, our board members and volunteers were putting on finishing touches. Stasie Maxwell, board secretary, arranged the raffle table that was overflowing with the generosity of local businesses who donated kindly and enthusiastically to our humble fundraiser. Taylor McAllister, student board member, organized the merchandise table where our new biodiversity t-shirt was proudly on display. Meanwhile Daniel Collay, board chair, and Rob, also a volunteer of extraordinary enthusiasm and muscle power, set up the last remaining chairs and unloaded plates and glasses that were generously lent to us by Willow-Witt Ranch. There was a final hush as the last detail was moved into place. The table was set, both literally and figuratively, for the 2023 Friends Annual Celebration.

The atmosphere was friendly and jovial as the lawn was slowly filled with attendees. The guitar music of Greg Starbird drifted through the background. Even though many people came from different towns and led different lives, they all shared something in common: A love and appreciation for the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Walking around, we saw many familiar faces from this past year’s Hike & Learns, Sunday Hikes, and Stewardship Days. The same people who we spent hours together sweating and removing barbed wire fencing, or stooped over an old stump examining a burn scar, now enjoyed refreshments and reflected on a year well spent.

Mike, another amazing volunteer, was armed with a practical apron and broad smile, offering an “arm’s length” of bright red raffle tickets as people strategically made their selections and put their tickets into metallic silver cans. On a nearby table, a crowd was clustered around a map of the Monument where pictures of beavers waited along the margins to be moved onto the map in exchange for a small donation. Teresa Coker, board member, explained that it was in support of a future “Beaver Scavenger Hunt '', an important first step in the Friend’s new stewardship program in partnership with Project Beaver.

Soon enough, armed with warm spiced cider and a colorful salmon dinner from Maren Faye catering, everyone found their seats. The lucky raffle winners were drawn and then Collette took the stage. It isn’t usually easy to distill an entire year of an organization’s changes, accomplishments, and future goals into a succinct and interesting presentation but Collette did so admirably. Not only did she highlight our successful programming, including our Hike & Learns, Friends Research Fund, and Monument Days with the Crest, she also celebrated the hiring of Program Coordinator, Zaynab Brown, and temporary Operations Manager, Meaghen O’Rourke. We even got to commemorate our new office! Finally, Collette addressed what all of the cute little beaver cut outs had been hinting at: Our beaver habitat stewardship program in 2024. With this, Jakob Shockey took the stage.

It is hard not to fall in love with beavers when you spend just a little time learning and getting to know them. This is particularly true when they have an advocate such as Jakob Shockey, executive director of Project Beaver. Jakob took us on a journey through the historic presence of beavers in our local area and in the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Not only were we all impacted by the tragic loss of their numbers due to removal by white settlers, we were also impressed with their promise for the future of riparian restoration. From table to table there was a palpable excitement, a drive to help these unassuming rodents take charge of our waterways once again.

As Jakob wrapped up his presentation, the air had taken on a decided chill and the sun had disappeared quickly as it so often does in the mountains. The Friend’s 2023 Annual Celebration had officially come to a close and attendees claimed their raffle prizes and headed back to their vehicles for a curvy drive back down to the valley. However, the night wasn’t yet over for our volunteers and their families. Quickly, everyone jumped into action and started taking down decorations, piling tables, and putting back chairs. Even the small kitchen in the school was bustling with brave volunteers tackling piles of dishes. It is always surprising to me how an event that took months of planning and hours of setting up can come down in what seems like mere moments.

Soon, it was quiet and dark, the moon hidden behind clouds. The towering ponderosa pines were no longer casting a shadow but their presence was noted nonetheless. The guests and volunteers had gone home, but all left with a renewed sense of community and anticipation for what was to come.

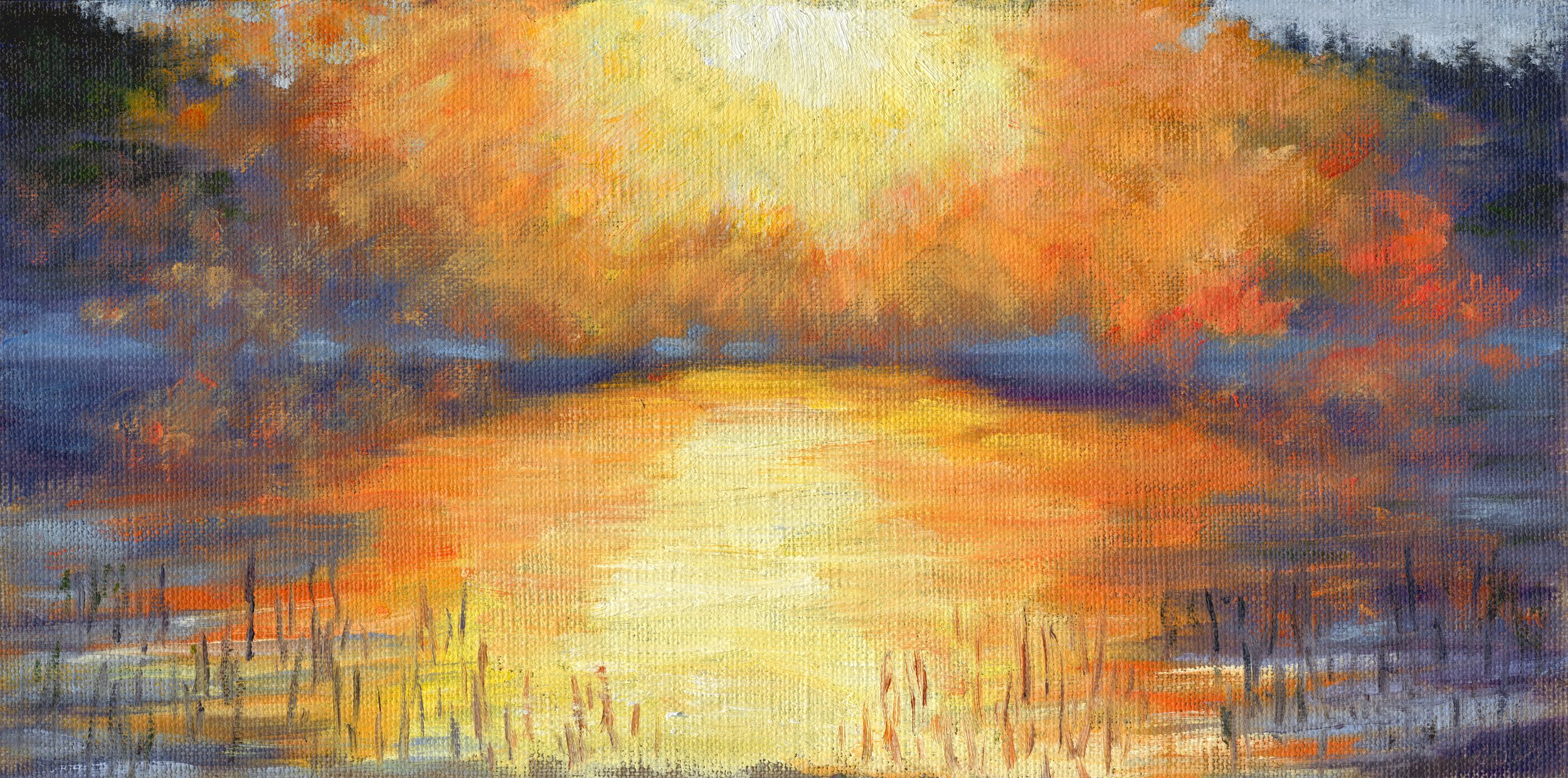

Artist-in-Residence Shares Her Experience

I served as Artist in Residence in Cascade Siskiyou National Monument during the last week of June, 2023. It was a glorious time, with spring flowers and new growth everywhere, and the weather was pleasant. The strongest impression I had, though, was that everything was green. Overwhelmingly green.

I live on Washington’s dry side where the predominate color is desiccated brown. There really aren’t many shades of brown: light brown, medium brown, dark brown, brown in sunlight, brown in shadow. And for most of the year, the occasional touches of green are faded, like the pale green of sagebrush. In contrast, green was not at all reticent at Cascade Siskiyou National Monument in June.

Cascade Siskiyou has a full palette of greens. “50 Shades of Green” could have been the title for at least one of the paintings! I frequently work en plein air and try to replicate the feeling of a specific place. It’s challenging when everything is green because green comes in such an amazing variety: Pine tree green is not fir tree green; grass green is not moss green; dogwood tree green is not aspen tree green, along with random touches of contrasting burnt orange and russet. Furthermore, green is not easy to reproduce. Yellow plus blue is green, of course, but which yellow (bright cadmium, earthy yellow ochre) and which blue (sky blue cerulean or deep-water ultramarine)? Each combination produces a different range of tones. And any yellow-blue mixture must be moderated with its complement, a red hue, so it looks like it belongs in nature rather than in a coloring book.

So I spent my time in the Monument painting green in all its glory. I painted the variety of greens in the forest and in the reflections in Hyatt Lake, and I painted the delicate soft pale green of mullein and the chartreuse green of moss on a fence. There were more greens, lots more, reflecting the variety of plants and ecosystems in the Monument. I suppose the overwhelming green was, in part, a seasonal condition and that summer, fall, and winter would bring a different set of colors. And that will be a challenge for another Artist in Residence!

Words and paintings by Leslie Ann Hauer

2023 Nature Camp - An Unforgettable Season!

The 2023 Monument Days with The Crest’s Nature Day Camp have recently concluded an unforgettable season. The program spanned seven weeks and served about 150 students aged 5 to 12. These days provided the perfect backdrop for young explorers to forge connections with nature, engage in captivating discussions, and cultivate collaborative skills. Participants were not only immersed in the beauty of the outdoors but also had the opportunity to deepen their understanding of the environment through hands-on activities and educational sessions. The diverse range of age groups allowed for the exchange of unique perspectives.